It's time again to rewrite some local history.

Renowned local historian Jerry Reynolds wrote about a turn-of-the-(20th)-century gunfight in Acton in his 1992 book, "Santa Clarita: Valley of the Golden Dream." Reynolds states:

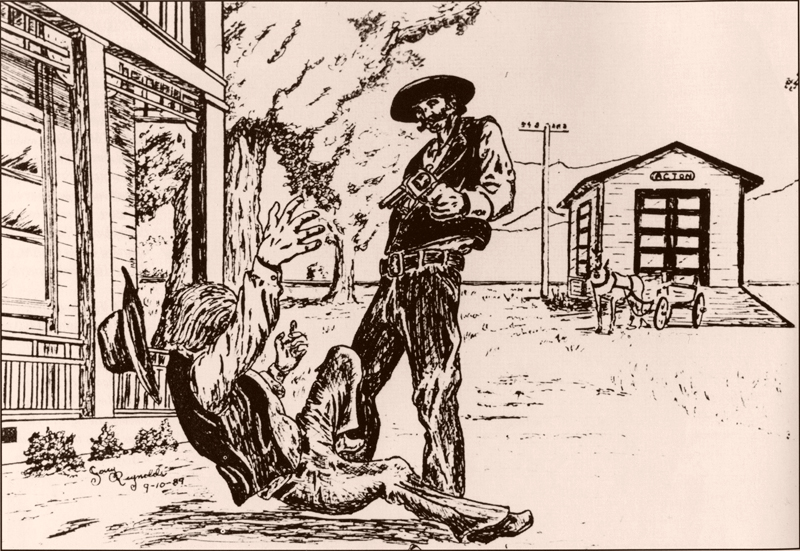

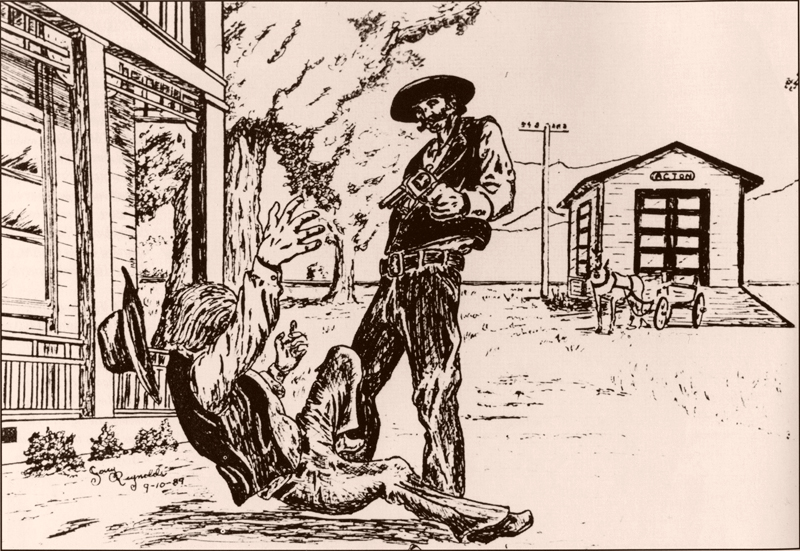

Jerry Reynolds' depiction of the end of the Crown Valley Feud — and of William Broome. Click image to enlarge.

|

A great many of the early settlers of Acton were of German descent, from upstate New York. A leading citizen of this frugal, hard-working, well-behaved faction was William Broome — farmer, church deacon, school board member and honorary mayor.

During the 1890s newcomers began to arrive, mostly from the south. Their leader was W.H. Melrose, called "Rosy" by his friends. Melrose was a big, fun-loving Kentuckian who was addicted to practical jokes, besides being quick on the draw and deadly accurate. He easily ingratiated himself with county officials, and on May 10, 1898, his wife, Flossie A. Melrose, became postmistress.

The trouble seems to have started when Broome's snorting, snarling pit bull attacked Melrose's good-natured dog Llewellyn, prompting Rosy to shoot Broome's offending animal. Broome had Melrose arrested, but at the trial the local school teacher, Minnie Boucher, backed the Kentuckian. Naturally, the German element tried to get Boucher fired. Broome even branded her a "railroad whore." Acton became an armed camp and the schoolmarm was transferred.

On February 28, 1905[1], Melrose and Broome faced each other on Acton's dusty main street. The guns roared and William Broome dropped with five well-placed bullets in his chest.

A review of The Los Angeles Times newspaper archive from that period fills in more details and shows a far more complex and long-running feud between the two men that started with the trouble between their canines.

Norman M. Melrose apparently was not the first person to have a run-in with Broome.

William H. Broome arrived in Acton from Bisbee, Ariz., in 1900. He was the night operator and railway telegrapher for the Southern Pacific Railroad at Vincent (between Acton and Palmdale). On Dec. 23, 1900, while on his way to work, Broome was accosted by one M. Baner, who leveled a shotgun at him and ordered him to halt.

Not to be bested by this assailant, Broome threw himself to the side of his horse and spurred the animal into a run. One shot from Baner's weapon passed harmlessly over the horse's back. Broome made it safely to Vincent Depot but there was confronted by the day operator, T.L. Wilson, who refused to let him in the station. There had been bad blood between the two operators. Broome was forced to ride off on his horse to face the shotgun-wielding Baner. He survived yet again, and Baner was brought to the Superior Court the next day and charged with assault with intent to murder Broome.

Broome and the Actonoma Oil and Mineral Development Co.

A few months after surviving the altercation with Baner, Broome was reported to be trying his hand in the oil business. He purchased a $3,000 drilling rig to be used in a new oil field in the Cedar Mining District between Acton and Vincent.

Intent on drilling for large quantities of pure parrafin oil, Broome staked claims on 2,200 acres in the area for a partnership between himself and his Southern Pacific Railroad friends, including some of the best known conductors on the line between San Francisco and Los Angeles.

Broome would become the largest holder of oil claims in the region. By April 1901, Broome and his associates had gobbled up 21,000 acres of land, which was astutely appropriated before any potential competitors even knew what he was doing. The next month he filed articles of incorporation for the Actonoma Oil and Mineral Development Co., with capital stock of $1 million when fully subscribed.

Meanwhile, Melrose developed a habit of writing to Broome's business clients, accusing him of being a swindler and bunco man who was trying to sell them worthless oil stock and land. Broome eventually sued Melrose for libel but lost the case and felt increasingly bitter toward Melrose.

The Dog Incident and Courthouse Monument Dispute

The infamous dog incident between Broome and Melrose was reported in an inconspicuous paragraph in The Los Angeles Times on July 7, 1901:

"SHOT A DOG. Complaint has been filed in the Township Court charging N.N. Melrose with killing a dog belonging to Guy L. Broome."

The feud had begun. The Broome and Melrose families accused each other of killing their domestic animals. Broome had Melrose arrested for killing a Saint Bernard dog. Several lawsuits were filed.

Democrat Stephen Mallory White (1853-1901) was an eminent criminal defense attorney who served as Los Angeles County District Attorney (1882-84), state senator

(1887-91) and U.S. senator (1893-99, retiring a year before the expiration of his term and leaving the office vacant). Melrose objected to a public memorial to White,

arguing that even a memorial to the "illustrious name" of the recently assassinated Republican President William McKinley, whom Melrose said was more

highly revered, would set a dangerous precedent. Broome was livid.

|

In November 1901, the two men found themselves on opposite sides of a dispute over the placement of an $18,000 monument in memory of the recently deceased U.S. Sen. Stephen M. White, D-Calif., on the grounds of the county courthouse.

Then serving as postmaster of Acton, Melrose sent a letter to the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors stating that the citizens of Acton had asked him to forward their protest against the placing of the statue. A few days later, Broome wrote to the supervisors, claiming, "I wish to advise you gentlemen that such is not the fact and that from all accounts Melrose took it upon himself to address your board without even as much as letting anyone here know his intentions. Such a prevarication we consider little short of criminal."

Two days later, Broome wrote another letter to Judge Allen of the United States Government Reserve Board[2] in which he states: "Upon my return home after meeting you, I find that the communication N.M. Melrose wrote to the Supervisors, and of which you spoke, is a prevarication of the first water. None of the citizens here, as far as I am able to find out, ever requested him to write a thing against placing the White monument on the Courthouse grounds, and we presume he wrote it all himself, not expecting it to come out in print where we could see it. … We have not come across a person Melrose even consulted about the subject, and hope the honorable Board of Supervisors will kindly put it down as another of the numerous fairy tales of which Melrose is guilty."

The Fistfight

Less than two weeks later, the dispute came to a head when Melrose and his wife were arrested for attacking Broome when he came to retrieve his mail.

Broome accused Melrose of striking him in the face several times with a blunt instrument. He claimed that Mrs. Melrose reached through a window and grabbed one of his arms so he could not defend himself. A crowd gathered to stop the fight, and Melrose was accused of beating Broome in the face with his fists while his wife held on to him. Broome was hospitalized with a badly injured right eye. He had Mr. and Mrs. Melrose arrested and charged with battery.

Melrose had a different story. He claimed Broome started the fight when he went to give Broome a letter that had been received improperly sealed. Broome had already suspected Melrose of tampering with his mail in order to get the addresses of his business clients. The fight spilled out into the street and Melrose pinned Broome to the ground. Melrose released Broome, who again attacked him, and then fought back, leaving Broome with a severe eye injury. Melrose further claimed that his wife was not involved in the incident.

The newspaper further reported: "The trouble between the two men is of long standing, and its ramifications are such that to explain it all would require no small volume. …"

The Acton Gunfight

And then there was the famous gunfight. Straight out of the Wild West, it occurred Jan. 20, 1903.

A telegraph dispatch from nearby Ravenna provides a version of the incident: "W.H. Broome was murdered by N.M. Melrose, at Acton, at 5 o'clock this afternoon. The men were enemies. Broome had just returned from a hunting trip, and was standing in the street, shotgun in hand. Melrose ran into him from behind with a wheelbarrow. Broome put down his gun and started to take off his coat. Melrose drew a revolver and shot Broome in the back of the head. Broome fell. Melrose then emptied his revolver into his prostrate form, beat him with a revolver and then kicked him." Ten minutes later, Broome was dead at age 35.

Immediately after the shooting, Melrose drove away in a buggy with his wife and headed for Lancaster, where he turned himself in to the justice of the peace of Lancaster Township. There he gave his version of the gunfight to a Times correspondent.

Melrose said Broome had been shooting pigeons in and around Acton with some saloon buddies. Shortly before 5 p.m., Melrose headed home with a wheelbarrow from a nearby field where he had been repairing a windmill. He was intercepted by Broome, who blocked his path, cocked his shotgun and shouted, "You dirty coward, I've a notion to blow your head off." Melrose made no reply and tried to get around Broome to a street near his home.

Broome proceeded to put down his gun, take off his coat and challenge Melrose to fight. Melrose attempted to place his wheelbarrow between Broome and his gun, which was now 10 feet away. Both men made a run for the shotgun, and while each had hold of it, one barrel was discharged. No one was hurt, but Broome took full possession of the gun, backed away, and tried to shoot Melrose with the remaining barrel.

Melrose drew his revolver and first shot into the ground, trying to get Broome to desist. Having failed to stop Broome, he fired again, this time striking Broome in the head.

Melrose claims that after Broome fell, he still shouted, "The ———— ———— is trying to kill me, but I'll kill him first."

Melrose claimed he took the shotgun away from Broome and then called the justice of the peace at Lancaster to notify him of his impending surrender. He confidently claimed justifiable homicide in self-defense.

The Coroner's Jury

The next day a coroner's jury convened in the dining room of the Acton Hotel and concluded that Melrose had inflicted gunshot wounds into Broome with "malice aforethought, and with the intent to kill and murder."

Six witnesses testified as follows: Melrose purposefully ran into Broome with the wheelbarrow. Broome turned around and called him vile names with the intention of starting a fight. Melrose said nothing and headed up a side street followed by Broome, who continued to hurl epithets at him. At the boundary of the hotel grounds, Broome leaned his gun against a fence, took off his coat and said, "Come out and fight fair and square" and shouted "coward." Melrose put down his wheelbarrow, drew his 32-caliber revolver and shot Broome in the back of the scalp as he turned and ran. As Broome fell to the ground, Melrose ran to him, beat him two or three times on the head with the revolver and then fired three shots into his body. Melrose then kicked Broome in the side and walked away with his shotgun despite the protests of several bystanders. The witnesses testified that there was no struggle for the gun as claimed by Melrose.

After the shooting, the townspeople of Acton expressed an ongoing fear of Melrose. They were taken aback by his nonchalance and indifference to the shooting. Acquaintances of the two men described how "Broome was a quick tempered man, but soon got over it, and was very kind-hearted; Melrose was always cool and collected, and said little, but once injured, cherished his revenge always."

To be continued with the arrest and trial of Norman M. Melrose.

1. Reynolds' date of 1905 is in error. The correct date is Jan. 20, 1903.

2. As reported in the Los Angeles Times, Nov. 19, 1901. We don't know what the "United States Government Reserve Board" is.

Alan Pollack, M.D., is president of the Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society.