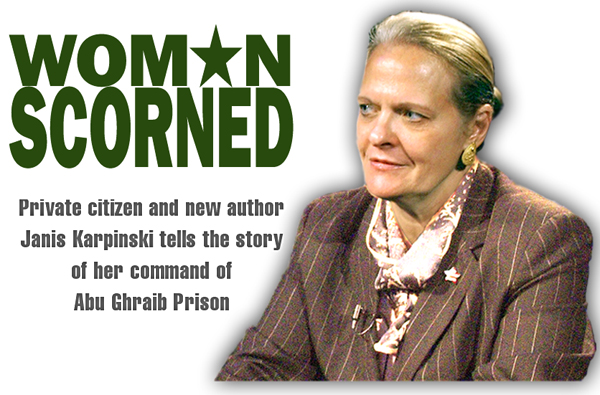

SCV NEWSMAKER OF THE WEEK:

Janis Karpinski

Former Commander, Abu Ghraib Prison, Iraq

Sunday, November 13, 2005 Interview by Leon Worden

Interview by Leon Worden

Signal Multimedia Editor

(Television interview conducted November 4, 2005)

"Newsmaker of the Week" is presented by the SCV Press Club and Comcast, and hosted by Signal Multimedia Editor Leon Worden. The program premieres every Wednesday at 9:30 p.m. on SCVTV Channel 20, repeating Sundays at 8:30 a.m. Signal: Thank you for coming to Santa Clarita.

Karpinski: Glad to be here.

Signal: You were the first woman in U.S. history to command troops in a combat zone, and you were the first general in U.S. history to be stripped of your general officer rank.

Karpinski: That's correct.

Signal: Were you wronged?

Karpinski: Absolutely. They picked a scapegoat and stuck to it. And they were going to spin the story to support their decision.

Signal: You've written a new book, "One Woman's Army: The Commanding General of Abu Ghraib Tells Her Story." But you were more than just the commanding general at Abu Ghraib.

Karpinski: Right.

Signal: What was your assignment in Iraq in 2003?

Karpinski: Well, in Iraq I considered myself very fortunate to be able to deploy, to join my units in Iraq, because I was selected for promotion and then I was told, "I have good news and I have bad news. The good news was, you've been selected, the bad news is, your units are already in Iraq — but they're coming home." So I said, "Then what's the bad news?" "Well, do you want to go and join them, or do you want to wait until they come home to meet them?" And I said, "No, I'd like to go." And the person making that phone call to me was surprised. "You really want to go?" And I said, yeah, what a great opportunity to see how soldiers perform during their mission and in the field, in combat. Signal: You're Army Reserve; you were in charge of an Army Reserve brigade. You were in charge of all 17 U.S. prison facilities in Iraq?

Karpinski: Yes.

Signal: So not just Abu Ghraib?

Karpinski: No.

Signal: Isn't it normally the case that if you need extra bodies, you call up the Reserves? Isn't it normally the job of the regular Army to run detention operations and things like that?

Karpinski: Well, some of those things are correct and some of them are preconceived ideas. In fact the National Guard units are the reserve component element that has a support mission, so you'll have infantry units, you'll have Army units in the National Guard. In the Reserve you will not. They are doing support and combat support missions. A prisoner of war camp, for example, traditionally has always been located very much to the rear, or in a safe area. In World War II you'd have prison camps in Arkansas, for example — very much removed, because they're be in a safe place. Signal: With the war declared over in May, this was just supposed to be a mop-up operation?

Karpinski: Correct. Sustainment operation. It really is when police operations would go into full tilt. Signal: Where does Sanchez fit into this?

Karpinski: Lt. Gen. Sanchez was the commander of all of the forces in Iraq. He was the senior Army commander and he was the headquarters commander. We were assigned to the CJTF-7 (Coalition Joint Task Force-7) for operations in Iraq, his theater.

Signal: You were under him?

Karpinski: Right.

Signal: And you were in charge of running the prisons?

Karpinski: Right. With a schedule, by the way, of turning it back over to the Iraqi people, according to Ambassador (Paul) Bremmer's plan, in 90 days or less.

Signal: The soldiers who have been court-martialed in connection with the abuses at Abu Ghraib since your last "Newsmaker of the Week" interview 16 months ago, such as Charles Graner and Lynndie England, were under your command.

Karpinski: Right. They were assigned to a unit that was under the brigade.

Signal: They're the ones who were responsible for the photographs that everybody has seen.

Karpinski: Well, they've been accused of being responsible for the photographs. But if we take it down to the very basics, Lynndie England did not deploy to Iraq with a dog collar and a dog leash. So obviously somebody gave her those props that we see in those photographs that are now seen around the world.

Signal: Did those abuses all happen in one night?

Karpinski: Well, the date stamps on the photographs, to my understanding, would say that they all happened on one night.

Signal: Where were you on that night?

Karpinski: Well, I wasn't out at Abu Ghraib, because I wasn't allowed to be out at Abu Ghraib at night. And that policy was not just directed to me, exclusively; it was directed at anybody (for whom) it was not essential to travel in the hours of darkness, after sunset, before sunrise. Karpinski: You know, I've said — and I don't mean to simplify it, because I'm not going to abandon those soldiers and say they really weren't my soldiers. They were assigned to one of my companies. But they were told by not only the commander of the Military Intelligence brigade, but by another lieutenant colonel who was not working for the commander of the Military Intelligence brigade but supervising cellblock 1A and 1B — he told them that he had the authority to give them orders and work instructions. Signal: But you were in charge of these soldiers. You were in charge of the 800th Military Police Brigade, which includes all Military Police personnel. Isn't Janis Karpinski ultimately responsible for the actions of all of her Military Police personnel?

Karpinski: Absolutely. But I have a chain of command, too. And it goes up. My chain of command included Gen. Wodjakowski, the deputy commander to Gen. Sanchez; Gen. Sanchez; Gen. Abizaid; (Defense Secretary Donald) Rumsfeld — and these people have just completely walked away from any responsibility whatsoever. Signal: Where should the buck stop?

Karpinski: Well, I think there's plenty to go around. There have been many failures in all of this — principally, in my opinion, leadership failures, from the very top levels; and clouding the lines of the chain of command, intentionally. Transferring a detention operation to the commander of a Military Intelligence brigade goes a long way toward clouding judgment, and I think it should go all the way to the White House.

Signal: Let's go up just one notch. Janis Karpinski didn't go to Lynndie England and say, "Here, put a leash on this detainee." Neither did Gen. Sanchez.

Karpinski: Correct.

Signal: Is Gen. Karpinski any more or less responsible in this than Gen. Sanchez?

Karpinski: Well, I don't want to sound like I'm trying to defend myself or deflect blame; I want to share it. We have different levels of responsibility in this. But Gen. Sanchez's signature is on an eight-page memorandum authorizing harsher interrogation techniques to include the use of dogs, and unmuzzled dogs with his specific permission. His signature is on that memorandum. And it was distributed to the Military Intelligence brigade, to the units that were doing interrogations out there. So he knew, because he signed it. Signal: You were the commander of the Military Police brigade but not of the Military Intelligence personnel who were operating inside your prison.

Karpinski: That's correct.

Signal: What was the date of this night that these photographs were taken?

Karpinski: The date stamp on the pictures that I saw was the 14th of November of 2003.

Signal: The prison was still under your command at that time.

Karpinski: That's correct.

Signal: A few days later, the prison was no longer under your command?

Karpinski: That's correct. It was transferred — again, by official order; they call it a fragmentary order, and it changes some instructions that you're operating under. I was responsible for Abu Ghraib among the 17 prison facilities we were responsible for. So this order released me from control — and it does: It transfers control, by the order, to the commander of the 205th Military Intelligence Brigade, responsible for all detention operations and all personnel that are Abu Ghraib.

Signal: Was there a connection between this night of craziness on Nov. 14 and the removal of Abu Ghraib from your command on Nov. 19?

Karpinski: Well, when they transferred the control of the prison by the order, I wasn't even in Baghdad at the time. So there was no discussion — once again, no plan, no "Let's make sure that the lines of command and authority are clear." There was no discussion. It was simply transferred. Signal: So Pappas, the Military Intelligence commander, is telling you that he, Pappas, is now in charge of Abu Ghraib.

Karpinski: That's correct.

Signal: Over these last couple of years, has Pappas been punished?

Karpinski: He has. He was not suspended from his command during the course of all of these investigations. He was interviewed many times, I'm sure, and he was eventually relieved from his command. He was not reduced in rank, but he was fined a certain amount of money for two months, and he's still on active duty. He's still serving in the military, as are all the other players in this.

Signal: You were not discharged, honorably or otherwise; you retired.

Karpinski: Right.

Signal: Do you draw a pension? Are you still in good graces with the U.S. military?

Karpinski: I guess some people would have a different opinion on it, but I applied for my retirement; my retirement was approved, and I don't draw any pension or any retirement money until I'm 60, because I was a Reservist. That's the rule that applies.

Signal: But you will draw a pension.

Karpinski: Yes, eventually I will. Right.

Signal: These photographs were taken Nov. 14; you found out about their existence, or about a problem in general, when?

Karpinski: On the 12th of January of 2004.

Signal: Do you have any information to suggest that anybody above you, or parallel to you in a command position, knew about them earlier?

Karpinski: Well, I have seen, I've read, sworn statements from a person identified as a Military Intelligence interrogator — no indication whether it's a warrant officer or a commissioned officer or a sergeant or an enlisted solider, but identified as a person from the Military Intelligence brigade who was in what they called the Intelligence Coordination Element Office; it was a top-secret facility out at Abu Ghraib. Gen. Fast went out to visit the interrogators, and this was in early November —

Signal: Fast was in charge of intelligence.

Karpinski: She was the intelligence officer for Gen. Sanchez. She was a brigadier (one-star) general at the time. And she saw on somebody's laptop computer there, a screensaver, and it was the pile of these naked detainees.

Signal: She supposedly saw this when?

Karpinski: In early November. The date in the statements says approximately the 6th of November. Signal: What is she doing today?

Karpinski: She is a two-star (general) today. She has been promoted and she is commanding Fort Huachuca, which is the Army's Military Intelligence school and center (in Arizona).

Signal: So it wasn't until recently that you found out that maybe Fast saw a photograph back in November 2003.

Karpinski: Right.

Signal: So after January, when all hell broke loose — privately, since it didn't break loose publicly until March or April 2004 — you weren't in charge of the prison but you were still in charge of the Military Police soldiers. Were you instructed to discipline them somehow?

Karpinski: No. In November there was a transfer of responsibility in addition to everything else going on. But from September of 2003, following Gen. (Geoffrey) Miller's visit — Gen. Miller was the commander of Guantánamo Bay. He was sent to Iraq ... to work with the Military Intelligence interrogators, to get them to learn ways that were more effective in getting actionable intelligence. So he comes, he leaves, he wants Abu Ghraib, to make it the intelligence center for all of Iraq. After his visit, things started to move definitely in that direction. Signal: But these photographs weren't directly related to what Miller and Pappas and the intelligence people were doing on the interrogation side, were they? They were photographs taken by soldiers on this night of craziness. Those were two different things, were they not?

Karpinski: Well, interrogations, to my knowledge — and I base that on what I was told by the commander, the executive officer, the operations officer, and the Military Intelligence brigade — interrogations were conducted outside of the cellblocks completely. There were two interrogation facilities at Abu Ghraib that were especially constructed for interrogations, and all of the bells and whistles to make sure interrogations were done correctly — one-way mirrors, those kinds of things; it was just set up that way. Signal: There is no interrogating happening in a pile of prisoners.

Karpinski: That's correct. The person who was showing me these photographs was the commander of the Criminal Investigation Division; they were responsible for doing the investigation. And remember, this is the 23rd of January. So I heard about it first not from Gen. Sanchez or anybody in a chain of command; I heard about it mentioned by the same (Army CID) individual. He was going in to brief Gen. Sanchez on the progress of the investigation. Signal: Part of what they were supposed to know about decent and humane treatment was training that ultimately you were responsible for making sure they had. In his investigation of the actions of your 800th MP Brigade, Maj. Gen. Antonio Taguba criticized you for not providing adequate training and supervision for these soldiers. Were the soldiers not equipped with the proper training ahead of time, back at Fort Bragg, before shipping out to Iraq?

Karpinski: They were trained for a mission, prisoner-of-war operations. And detention is not detention is not detention. There are different kinds of detention. There are brigades and units in the Army and in the Reserve components and in the National Guard that do confinement operations, which would be more like what we would be doing eventually in Iraq. But prisoner-of-war operations are different. Different rules apply. Geneva Conventions, primarily. Signal: Is Janis Karpinski in any way responsible for violations, on anyone's part, of the Geneva Conventions?

Karpinski: The violations of the Geneva Conventions? Absolutely not. In detention operations, that I am very familiar with in Iraq, there were no infractions. Signal: The way that it has been characterized in the news, it almost makes it sound like Janis Karpinski doesn't know what she's doing, doesn't know how to run soldiers. But not just anybody makes general; you must have demonstrated some kind of command ability.

Karpinski: Right. At every level of command in the Army.

Signal: What is your background?

Karpinski: I was a company commander, and when I was a company commander there had never been a female company commander in that unit before who did these so-called honor guard ceremonies, and I had to experience that whole turbulence with, again, another combat arms officer who said, "You can't do the ceremonies. We've never had a woman do the ceremonies before." We've overcome that barrier; we move onto the next one. Signal: Between the soldiers at the bottom of the ladder and you, there was a level or two of officers. They were not punished, were they?

Karpinski: No, they were not.

Karpinski: Right.

Signal: Only Janis Karpinski. Why?

Karpinski: Because Janis Karpinski was — people have said to me since then, "Are you sure you didn't have a target on your T-shirt?" I checked many blocks. I was the first female, and the only female, as you said, to command troops in a combat zone, and they didn't like that. This is still the "good old boy" network. This is still the last bastion of male control in the government, in the military. And Gen. Sanchez did not want to be the guy who was forever tagged with letting the first female general succeed in commanding troops in a combat zone. So he was determined from the very beginning to make sure — he didn't care how many new missions and unusual missions he threw at the 800th MP Brigade. He didn't care if we failed. But he wanted to make sure we didn't succeed.

Signal: Gen. Sanchez requested the investigation into the 800th MP Brigade. He requested specifically that it be conducted by somebody from outside of his chain of command, and that it should be "all-encompassing." That "somebody" ended up being Maj. Gen. Antonio Taguba, who was over in Kuwait. I have talked to Gen. Taguba. He described Sanchez as a "good friend." I asked Gen. Taguba why he didn't take his investigation beyond the level of Janis Karpinski. He said the scope of his investigation was limited to the 800th, and that he wouldn't have taken it higher "unless I was given permission and authorization to do so, and I was not given that." There were allegations within his investigation, certainly made by you, to indicate that his investigation should go higher. Who would have denied him authorization to take it higher than Janis Karpinski?

Karpinski: Nobody denied him authorization. He didn't look for it. And he has been able to hide under these limited parameters. Signal: What would you say to a young woman today who is thinking about joining the Army?

Karpinski: I would say: It's a great career. You will be able to do things and you will have opportunities in the military that you would not have anywhere else. Signal: Do you still support the war effort in Iraq?

Karpinski: I certainly still support the soldiers. And I know that every single day, they are facing obstacles and challenges that they never before imagined, even though they're the best-trained military in the world. Perhaps not adequately trained for insurgency operations, but maybe they are learning that on the run, too.

Signal: During the period in which the abuses were taking place, Saddam was still on the loose. There was intense pressure to get information out of people about where the next attack was going to come from. Today, soldiers are still dying in Iraq, in insurgent attacks. Did the Abu Ghraib scandal put a damper on our ability to gather intelligence? Are we not beating the crap out of enough people today to gain good, actionable intelligence and stop that next attack?

Karpinski: Well, we know from people who have done this for years and years and years — professional people who conduct negotiations, hostage negotiations, interviews of really bad thugs, when they are arrested or apprehended — they know, and they've said repeatedly, that torture and abuse is not effective. Not even with terrorists or suspected terrorists. Signal: You are not totally alien to the interrogation process; you had some intelligence experience in the first Gulf War, right?

Karpinski: I did, but not interrogations. I did targeting.

Signal: Did what you saw what happening in Iraq deviate from what you had seen in the first Gulf War?

Karpinski: Only in terms of senior people, to include Gen. Sanchez, senior people from the active component, primarily, who have abandoned their leadership decisions and are making decisions based on the political ramifications of their decisions.

Signal: If you join the Army, you've got to understand you are taking a risk.

Karpinski: Right.

Signal: What do you say to the Cindy Sheehans of the world who have lost kids? What does Janis Karpinski say to Cindy Sheehan about whether it was right or worth it?

Karpinski: I say, "Keep on doing what you are doing." Because it is something she is clearly committed to. It's a tragic situation for anybody — a parent or a spouse or a brother or sister or a loved one — to lose a solider in this war, in any war, in any situation. "Keep on, because you are so committed to it. It's your passion." Signal: Are there more Abu Ghraib photographs and videos that the public hasn't seen?

Karpinski: That's what they say.

Signal: Have you seen them?

Karpinski: No, I have not.

Signal: What is the legacy of Abu Ghraib? Today when people think, "military prison," automatically many think, "abuse." Those photographs have become a cultural icon. But what happened at Abu Ghraib is not what normally happens inside a military prison.

Karpinski: No, it isn't. No, it isn't. But we continue to see soldiers misbehaving, in a variety of situations. We have them burning bodies — perhaps they thought it was appropriate and perhaps it was their instructions — but then we see people exploiting that action in a negative way. We see soldiers who are under arrest because they raped — all five of them are under arrest because they raped a young woman. So something is off track from the very jump. Signal: Is it possible to get it back on track?

Karpinski: I don't know. When we are contracting out critical skills that the military handled before in a professional manner — for example in interrogations, when we are contracting out interrogation operations and then know that there are no rules that apply to contract interrogators, that they appear still to be above the law — we are not moving back toward center-line. We are moving farther and farther and farther off track.

Signal: What do you want people to take away from your new book?

Karpinski: They will see the truth. They will read the truth. And I want them to take truth away from that book.

See this interview in its entirety today at 8:30 a.m., and watch for another "Newsmaker of the Week" on Wednesday at 9:30 p.m. on SCVTV Channel 20, available to Comcast and Time Warner Cable subscribers throughout the Santa Clarita Valley.

This week's newsmaker is Janis Karpinski, former commander of the 800th Military Police Brigade and detention operations in Iraq, including Abu Ghraib prison during the period of detainee abuse. Questions are paraphrased; answers are presented in full.

So he said, "Well, OK, we'll see if we can make it work." And they did, and I joined them, and of course the units were deployed to do a prisoner-of-war operation mission. The war was declared over on the 1st of May, and prisoners of war then are released. So the units were all preparing to go home, and basically it was dropped on us that, "Not so fast. We have this new mission for you."

Traditionally, Reserve and National Guard units would be used that way, but not so in this case. They were used in — of course, the boundaries of the battlefield have been erased. Combat is everywhere. Insurgencies are taking place everywhere. So you can't define the forward edge of the battle area. You can't define a rear area any longer. It's everywhere, wherever the theater is. In this case, it was Iraq.

So now you have units that are deployed that are ill-equipped and less than perfectly prepared to engage any kind of operation in a combat zone.

The active component (regular Army) Military Police brigade that belonged to Gen. (Ricardo) Sanchez's headquarters was not capable or interested, quite frankly, in doing the detention mission. They were working with the Baghdad Police Department. So it became our responsibility because nobody else wanted to do it.

The main supply routes — the MSRs, as we called them — were very dangerous at night. The insurgents work very well in the cover of darkness, and the units that were out there patrolling them did not want to make a mistake of identifying a patrol that was a U.S. patrol or a convoy, like mine would have been, as an enemy or an insurgent, and then blowing us off the face of the map. So that would be applicable to anybody that was nonessential to travel to somewhere in the course of the evening.

So I wasn't allowed to go. Abu Ghraib was particularly dangerous at night, and I was told that I couldn't remain out there. So I didn't live out at Abu Ghraib. I just ran facilities out there.

Signal. When the scandal first broke, one of the initial reactions from the White House was that this was just a handful of soldiers who got out of control. Turn up the clock and Janis Karpinski is busted back to colonel. Is it not right for the commanding general to take the blame for the actions of the soldiers?

The civilian contractors said that they had the authority from the Pentagon to issue orders and instructions, and the Military Intelligence brigade commander said, "You are my soldiers now." Now, none of them told me those things. The soldiers didn't say, "Who do we report to?" And I don't know why they didn't report it to the chain of command, because I've never been able to speak to any one of them since they were removed from their positions out there at cellblock 1A and -B.

So you can't talk about a chain of command if you're not going to talk about the entire chain of command.

The intelligence officer, Gen. (Barbara) Fast, knew, because she made sure that Col. (Thomas) Pappas, the Military Intelligence brigade commander, understood, and he made sure that his interrogation teams knew, because he distributed the same memorandum to them.

They didn't distribute it to the 800th MP Brigade.

When I found out about it, I tried to get information first from Gen. Sanchez; he directed me to Gen. Fast; she lifted the order up in her hand — she was on the telephone, and she was pointing to it and shaking her head as if to acknowledge, "Yes, this was what happened." No explanation or anything, and again, no clarification. But Col. Pappas did ask for clarification since now he's in charge, and he was told, "You have control of everything. You own everything' at Abu Ghraib," is what he was told. And he repeated that, as did his executive officer, to me.

Shortly after that, Gen. Fast was allowed to leave Iraq for approximately two weeks to go back to Washington, D.C. When I spoke to the commander of the Military Intelligence brigade I asked him, "Where (is she)? I haven't seen your boss around lately." He said, "Oh. Gen. Fast? She is back in Washington. She's visiting the intelligence agencies there and schmoozing," in his words, "with the senators." I said, "Oh, to make sure her second star is confirmed?" He said, "Oh, no, ma'am, she's got that locked up. She's already working on the third star."

Our prisoner population, in terms of Iraqi criminal prisoners, was really diminishing. The majority of the people being held out at Abu Ghraib during October, November, December onward, were "security detainees," which was a new category of prisoners.

I was disciplining my soldiers, as I was in any other location. I talked to soldiers, I talked to prisoners, at every one of the locations I went to. I continued to go to the headquarters to ask for additional support, additional funding. We didn't have the basic supplies for prison operations. A change of jumpsuit colors was really out of the question; we didn't have one jumpsuit for each prisoner at that time. When I mentioned that particular thing to Gen. Miller, thinking, you know, this is a different situation than Guantánamo Bay; maybe you don't have that perspective yet, he said, "My budget is $125 million a year and I am going to give the Military Intelligence commander" — not me — "I'm going to give the Military Intelligence commander all the resources that he needs."

During that time frame we opened a very small portion of the inside cellblocks at Abu Ghraib. We had a press conference, we let the people go through and see the new way of running detention operations, and we really wanted to use that report to put Iraqis' fears to rest that Abu Ghraib was never going to be operational like it was before under Saddam. So that was the direction we were heading with detention operations.

So when I saw the pictures, my first reaction to them, after I got over the fact that I thought the world was spinning out of control, I said, this isn't interrogations. What were they thinking?

So on the 23rd, I see the photographs — I am shocked like the rest of the world was when they saw them four months later — and I am asking him almost rapid-fire, "What were they thinking? What's going on? Where is the military intelligence in all of this, and why are the translators in cellblock 1A?"

He said, "Ma'am, those aren't translators. Those are contract interrogators."

Where did contract interrogators come from? Well, many of them came — specifically were selected and came to Abu Ghraib at Gen. Miller's instructions, because they had experience down at Guantánamo Bay or in Afghanistan. And he said, "Well, you're right. We don't believe what we are seeing is interrogation. But they are certainly humiliating us and abuse of a different kind," and I didn't disagree with that — but at that time didn't get a full picture of what we were talking about, either.

Nobody was able to piece together for me why these soldiers would behave in such a way, what would make them decide to abandon everything they knew to be decent and humane treatment and do such a thing.

But it wasn't that soldiers were ill-trained. I didn't know most of these soldiers — any of these soldiers, except a handful — because I joined the unit after they were deployed, some of them for six months. So I didn't know; I can't say what kind of training (they had before shipping out.)

In cellblock 1A and -B, what those photographs (show) is that the Military Police soldiers were being used to enhance interrogation operations, to "set the stage" for more effective interrogations. In Gen. Miller's introductory briefing back in September, he said — when I raised those concerns, I said that the MPs are not moving any of our prisoners around in leg irons, or hand irons or bellychains; it wasn't necessary, and we didn't have that equipment anyway — he said he was going to give all of the training material necessary to Col. Pappas, the Military Intelligence brigade commander, and that they were going to conduct specific training for the MPs who would be responsible for enhancing these interrogations.

That training was never conducted. Those training materials were never made available to me, to my sergeant major, to the Military Intelligence brigade commander. So it was because they found themselves in a situation where they were learning on the run, and on the night shift.

I would tell you, and I have told many people while we were deployed, we are so close to being in violation of Geneva Conventions because the conditions were so austere. Prisoners are supposed to get medical attention, showers, the food — and we were just so far behind the power curve, because there was no planning for any of this. But we were not in violation of the Geneva Convention.

I was a parachutist; there were not record numbers of females that were interested or going into jump school. I commanded at the battalion level, a prisoner-of-war battalion, succeeded there, went on to be an operations officer in an MP-heavy brigade, was selected to be a chief of staff, and then subsequently another position as a chief of staff of the largest Reserve component regional support command in the Army Reserves. But I demonstrated leadership abilities in every one of those assignments.

Signal: Immediately above you there were more levels of general officers, and they were not punished.

Signal: Immediately above you there were more levels of general officers, and they were not punished.

But right there. Right there is the first indication of who they were looking for, what scapegoat they wanted to find. Because he wasn't told to go and find out how these pictures happened. He was told. "Investigate Janis Karpinski and the 800th MP Brigade, and show them those pictures, and this is the result of her failed leadership."

So you (Taguba) are already prejudiced. You want to impress your good friend, Gen. Sanchez. You are hopeful that he will get his fourth star and somehow he will return the favor and you will get your third star. So again, this whole network of favoritism is taking place.

I will tell you that the only comment that Gen. Sanchez, in his brief comments to me, when I finally saw the pictures — he didn't want to talk about them. He didn't want to talk about how this happened. He said to me at one point, "Do you what this will do to my Army?" As if I was in another Army. And then, during the course of Gen. Taguba's investigation, or his interview of me down in Kuwait, at the end of the interview he used the same expression: "Do you know what this will do to my Army?" Again, as if I was an outsider and you're never coming in.

But I would also say: Go into this with your eyes wide open. Make sure you have weighed the pros and the cons in all of this. Make sure that this is something that you are really going to be strong enough and committed enough to do, and go into it with the full realization that there is at least a 50-50 chance that you are going to be sexually harassed, sexually assaulted or raped by your fellow soldiers.

The most productive results are from an effective dialogue. Now, maybe people don't like the thought of anybody sitting down with a so-called terrorist and saying, "So how is the weather?" But that's the most effective means of obtaining information.

People need to — now, all across the country — need to be facing not a political view, but reality. Thousands of Iraqis have been killed. Thousands of Iraqis continue to step up to the plate, to join the police force, the military. But as of a week ago, we know that there are some questions about the validity of actually going to war.

How deep does the deception go? And if it is a deception — if it is a deception, if the yellowcake document was forged and there was no real reason, everybody knew in the White House that there was no WMD, why did we go? Why? What is the purpose, then? If not this, then make us understand what.

But we are too far into this to just say, OK, everybody needs to come home. Stop the war, we're going to go home. Because if — and Cindy Sheehan's partial concern is for the Iraqis, that there's been thousands of them killed in the course of this war — but there will be thousands more if we just simply pull out and abandon them. They'll have no chance at all.

We fractured this. We broke the plate, so we own it. And we have to make this right in some way. We can't even define what's right. We certainly can't define how much longer we are going to be there.

And then you give the soldiers, or Marines, or whoever they might be in the military, you give them very specific training. They learn how to salute; they learn how to say, "Yes, sir," "Yes, ma'am;" they understand the chain of command, and then you deploy them to a combat zone where leadership really needs to step up to the plate. And it isn't there. They're being told things that were contrary to their very basic training that was memorized, in most cases, so they could execute it successfully.

©2005, SCV PRESS CLUB · ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.