|

|

|

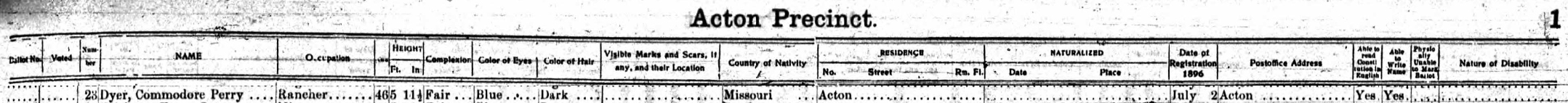

Sometime during 1881, Commodore Perry Dyer set his eyes upon the Santa Clara River in Soledad. "Grandpa Dyer, the Commodore, settled near the Mitchell place at the beginning of Soledad Canyon, about a mile near the beginning of the cemetery," said Francis Jansen, his granddaughter. There, Commodore Perry Dyer acquired land and built a cabin of his own on the bank of the Santa Clara River southeast of the Mitchell homestead. Eventually one of Dyer's daughters, Iva, married John Mitchell, son of Thomas Finley Mitchell. The last years of his retirement were spent with Iva and John at the Mitchell homestead. "When he got ready to pass on, he looked like Abraham Lincoln," except that his face was framed in gray hair with a beard and mustache. This is how Francis Jansen recalls her grandpa, Commodore Perry Dyer, who first settled in a place the Spaniards named Soledad, or "Lost Canyon."

Francis recalled her most prominent earlier memories of the Commodore, who wasn't really a commodore at all. He liked to call himself the Commodore, but his only known ship was forever landlocked; it was really a mere wagon that shifted from side to side, bending slightly to the crisp valley gales and the gait of the horses. Somehow, the lack of a real ship never bothered Francis, who as a 4-year-old enjoyed bouncing up and down on her grandfather's lap in the two-seat mud wagon with her father, William Allen Dyer, and the Commodore. Francis recalls vividly the excitement she felt as the trio made their way down the road, watching the back of the wagon slapping dry roads and stirring dust in its clouded wake. It was adventure to 4-year-old Francis, and more important, fun to ride. Anywhere. Anytime father and grandfather hitched up the wagon, Francis was sure to follow. When her father had groceries to deliver, both Francis and her grandfather provided companionship on the grocery route that took them as far away as Newhall to pick up supplies. Then the trio would return to the Sulphur Springs area near the Sulphur Springs School and the pioneer suburb of Lang. Jansen's father, William, the Commodore's son, established a store near John Mitchell's ranch in the Soledad-Santa Clara riverbed. There were originally two stores in the area. One was known as the Solemint store, and the other was William Dyer's. Dyer's family lived in a large, three-bedroom farmhouse, with windows framed in beige. The west side of the farmhouse served as a William Dyer's store. Their big, rust-red barn kept all of the store supplies. As part of his regular route, Francis' father took two trips each week to Los Angeles. His store contained mostly furnishings and household goods. Dyer's store, said Francis, "furnished Soledad and Aqua Dulce and up that draw, or creek, that was wide in some places." Twice each week, Francis' father would cut and deliver fresh meat and vegetables from the Sulphur Springs area to big, tall miners and their families working the borax mines in the Soledad area. The borax mines were located near Lang.

Long before there was a grocery route or hungry miners to feed and furnish, the Commodore's family made a memorable trek for a family reunion that was two long, hard years in wait. Ready for a reunion, in 1883, Ellen Ruth Dyer, along with her 9-year-old son, William Perry Dyer (Francis' father), younger sisters Ivy and Bessie, and finally 2-year-old James Thomas "J.T." Dyer, loaded all of the family's belongings and departed from the Missouri territory. Wagonmaster was 9-year-old William Allen Dyer, navigating the wagon across the Santa Fe Trail. Their trip began with the sale of the family's farm in a Missouri town now long forgotten — simply referred to as "the Missouri territory." (Public records show Dyer married Miss Ellen Allen on May 7, 1872, in Lincoln County, Mo.) With the farm sold and wagon outfitted with everything they owned, William loaded his ailing mother and his siblings aboard. Driven by a team of mules, together they trekked from Missouri to Kansas. In long, steady measure, William guided the wagon across the southern route, which crossed from Missouri through Kansas to the southeast comer of Colorado, through New Mexico and the Arizona deserts, and eventually on to California. This route, the Santa Fe Trail, was the most frequently traveled wagon route from 1820 until about 1870, when the Santa Fe Railroad was constructed. The burdensome weight of the wagons left straight ruts from their rolling wheels like cuts upon the palm of the prairie hills and plain. They are visible to this day. Thus, it was not so difficult for this boy and his family to follow the path that had been established long before them, first by wagons and later by the railroad. The sound of trains chugging down the track only served to spur the family on, closer to California. Not everything about their journey was harsh or brutal. During their passage, they would watch antelope tailing behind or alongside the family wagon. They would wait for great buffalo herds to pass, then allow them to move forward. Often, buffalo ran in mad circles, creating large bowls called "wallows." After great rains danced upon the plains and prairies, these wallows filled with water, effectively creating a polka-dotted landscape that stretched out to the horizon. With thoughts of their reunion with the Commodore, the family continued pushing on toward faraway California.

One of the trail stories that still survives today relates to their stay with a pioneer family on the plains. In those days, according to Francis Dyer Jansen, strangers were a welcome sight. As such, they were given all of the welcome one would expect to receive from a four-star hotel today in exchange for work, gossip and stories. One particular morning, the woman of the house woke everyone up with an apology for serving breakfast so late. It seems she was busy during the night giving birth and thus had overslept. After a heartfelt thank you, the travelers moved on. The rest of their journey to California meant crossing through New Mexico, where antelope still follow bicyclists across a gentle landscape painted with orange and pink sunsets, then through the harsh deserts of Arizona and California. They crossed the desert by day and slept by night. Water was a precious commodity for these travelers on their westward journey. Barrels of water were attached to the wagon, but conservation was a key to survival. Sometimes days would pass before water from a stream, creek or lake was found. In those days, with no continuous water supply, travelers did not bathe regularly. It was a dusty, dirty journey. They would wait until they neared a stream or river. Once they located such a place, they would bathe by swimming in the water. Traveling near water also meant a diet of fish. If travelers were not near water, they hunted for deer, quail, rabbits or whatever game they could find and consume. They camped every night. If the weather was good, travelers carried thin mattresses called pads on top of a tarp and slept beneath the stars. There were times when they stopped at people' s farms. Several times during the journey, the family slept in the hay inside someone's barn. Even when people had large houses, some had no room, so travelers slept in the barn. According to Will Dyer, there was no shortage of hospitality, and if there was bedroom, they slept in it. Usually there was a noon stopover, where the horses were released from their saddles to rest and graze while the family had luncheon. It was customary to use two mules to pull the wagons because they were larger, sturdier and stronger than horses. The mules and horses were tethered nearby, in the distance, or wherever they decided to settle for the night. Horses were tied onto the back of the wagon so travelers could ride into town or scout ahead. The family could usually see signs of civilization more than ten miles in the distance — signs such as smoke on the horizon. Will Dyer had a good sense of direction to lead the wagon. Sometimes they traveled together in a group for three or four days, and then they would break apart, depending on which direction they were headed. One group of travelers started in Missouri then went on to stay in Arizona, while others continued the journey to the west. The Dyer wagon traveled the farthest distance to California, which meant traveling alone for a time. Another danger faced by westward-bound travelers was fear of attack from an occasional mountain lion or coyotes, which were mistaken by children for small dogs. Not many people coming from Missouri had actually ever seen a mountain lion. Someone always rode shotgun to ward off threats. Ellen Dyer, who was unable to speak, traveling alone with her young children, faced all of these dangers. Imagine being out there alone in the dark of night, listening to wolves howl, perhaps leaves rustling in the wind, with only a campfire and the moon shining above. There was much relief when the travelers were reached Soledad. Years following the journey, family members recalled just how dangerous and difficult the trip from Missouri to California had been.

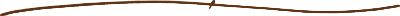

Francis Jansen's grandfather was surely a well-to-do gentleman. In Missouri, the Commodore was in the cattle business. Once in Soledad, he had a small supply route, selling notions to women such as groceries, sewing kits, hat pins and things women might need. There are only two known pictures in existence today. One (not locatable by the family) shows the Commodore with a shovel in his wheelbarrow, mining for gold. It is also possible he had some kind of agricultural business, since he owned a home and land not too far from John Mitchell's spread. The second picture shows the Commodore with his team of horses somewhere in the Soledad region. Ironically, the golden empire that grew from his settlement in California did not spring from the yellow mineral that comes to mind. While the Commodore's profession is not completely certain, all of his children, particularly his sons, went into the agricultural business, specifically beekeeping. Honey is the sweet liquid gold that continues to flow about the Commodore's family to this day. It was the precursor to a common thread that still binds his decedents together. Back then, beekeeping was an important agricultural product for many reasons. For one thing, when settlers did not have oil, they used beeswax to lubricate the parts of their wagons and other tools. Beeswax was also used for candles. Back then, nothing was wasted. This was especially true of agricultural products such as honey and cattle. Honey, not cane sugar, was the main form of sweetener. Used medicinally, honey was also applied to a variety of ailments. People treated their allergies not with inoculations or antihistamines like we do today, but with local honey, since it contains much of the pollen and irritants that create those allergies. Honey is still a recommended folk cure by some people for allergy treatment. The bee jelly, or larva, has great nutritional qualities and was used for vitamin supplementation. It is also used today in a variety of make-up products. The beekeeping business was an art, which also required many hard, sticky hours of labor on the road from the production by the bees to consumer product. One reason Commodore Perry Dyer may have settled where he did was the location of the Santa Clara River. Proximity to water was important for all settlers, especially so for those involved in agriculture. The river was an important water source for the beehives. To maintain production levels, bees and their hives require a year-around water source. Keeping the queen bee segregated from the worker bees was also important to maintaining the hive. When the beekeeper, or apiarist, went to collect the honey, he would first surround the hive with smoke. The smoke stunned the bees for a time, making them docile and easier to work with. Then the apiarist would collect the honeycomb containing this sweet liquid gold substance. The process enabled beekeepers to get near their hives without being stung. The hives were built from boxes that were layered on top of each other. The apiarist would collect the boxes on top with the honey. The box at the very bottom is the hive where the bees actually live. After separating the honey from the hives, the apiarist takes a knife and carefully makes a cut in the wax. Then he places the honey and the comb into a round cylinder which was steamed, while simultaneously spinning rapidly. The steam softens the wax comb while the centrifugal force pulls the honey from the comb. After several days in large vats, the honey settles, and any residue or sediment such as bee legs rises to the top. The residue containing bee larvae and bee body parts is then skimmed off the top of the honey, and the remaining liquid gold is poured into jars for sale and consumption. This was the agricultural dynasty begun by the Commodore's sons, William Allen Dyer and James Thomas "J.T" Dyer. Both William A. Dyer and his nephew, Willis (J.T.'s son), imported expensive drone bees from Italy. Francis Jansen recalls the fascination of workers at the local post office when these precious bees arrived. It was not just the drone bee cargo in these boxes that captured the attention of postal workers, but also the design of these boxes. Eventually, Willis Dyer learned how to produce his own genetic Italian drones, and the Dyer family no longer needed to pay the expensive costs to import them from Italy. Another reason why the California is such a special place for honey production is the growth of wild sage and buckwheat shrubs that sprouts in great abundance locally. California is still the only state in the union that produces the treasured sage and buckwheat honey especially prized by honey connoisseurs. These particular varieties of honey are treasured around the world as the finest-tasting honey produced anywhere. Commodore Perry Dyer' s great-grandson, George Dyer, and his wife, Sharon, were shipping honey to places as far away as Germany even into the 1970s. Today, money generated through beekeeping not only comes from honey production, but also from the rental of bee hives for use in pollinating farm crops such as almonds, cotton and oranges.

Commodore Perry Dyer's son William grew up and married Jessie Orena Bray, the daughter of a Southern belle, Annie Laura South Carolina Bray. Annie Laura's story adds its own indelible flourishes to the family history. Annie Laura was saved from her family' s burning plantation house which had been set on fire by Union troops. Her parents had become trapped in the burning mansion and perished. However, their daughter, 9-month-old Annie Laura, was saved by a brave, young African-American enslaved woman named Sukey. This remarkable woman took the baby to Atlanta where she was raised by an elderly aunt. After the war, Annie Laura was repatriated to her state, where she married a wealthy Yankee when she was 12. At age 13, Annie Laura gave birth to Jessie Orena Bray. According to Francis Jansen, Jessie Orena Bray grew up and married an Atlanta pharmacist named William Alexander Burt Johns. Desperately trying to escape her domineering mother, Jessie Bray fled to California with her husband. However, Annie Laura got wind of the scheme and was determined to stay near her daughter. Imagine how Jessie Bray's heart must have palpitated when, shortly after leaving the station, the moving train was stopped for her aristocratic and domineering Southern mother who proceeded to board the train with two wagon loads of household goods and two servants in tow. Jessie and her small family settled in Los Angeles where Johns opened a pharmacy at 7th and Broadway. As one might imagine, when the couple settled in Los Angeles, Jessie's mother purchased the house next door. Family lore insists it was Johns who tipped off his mother-in-law regarding his family's departure for California. Jessie had four children with Johns before he died. The story was truly a love-hate relationship, as only mothers and daughters can understand. William Allen Dyer became Jessie Orena Bray's second husband. She gave her new husband four more children of his own: Allen, William Perry, Ruth Ellen and Francis Dyer. Francis Dyer Jansen, now a proud 82, recalls her mother Jessie as having held highly spirited political debates over lunch with none other than William Randolph Hearst. Jessie played the role of Democrat in these heady and spontaneous political exchanges. Jessie and Hearst also enjoyed a hearty exchange of correspondence, but like many things created in the days of incinerators, the letters were burned as trash. Francis' only lasting memory of her grandfather was watching by his deathbed as he slowly faded over more than a week's time, and the ensuing funeral. She recalled how her mother and J.T. Dyer's wife, Mary Ritter Dyer, cared for him in his final days.

There was sadness, but there was also humor that emanated from the sometimes cantankerous 88-year-old Commodore Perry Dyer. At one point, the Commodore punted a wash pan full of warm water and soapy suds from the side of his bed to the doorway entrance of his room in the Mitchell house. Mary and Miss 'Rena, as Jessie Orena Bray Dyer was known, had quite a laugh over that one when it was over. Mary Ritter Dyer had spirit and was known for her great singing voice. Before marrying J.T. Dyer, Mary attended college. She came from her own well-to-do family, famous in Leona Valley. "Everyone loved to hear Mary's singing," remembers Jansen. Mary and Miss 'Rena were close sisters-in-law and good companions, especially during this difficult period for the family. Engraved more deeply in Francis' memory is the Commodore's funeral in 1925. For a few days after his death, his coffin remained in the two-window bedroom where he expired. A service was held at the Mitchell home. His funeral was so well attended that even today, in her mind, Francis can see the mile-long trail of dust from all of the people who followed in his wake. "Men mostly wore black hats. The women were dressed up. Everyone put up the Sunday-best go-to-meeting clothes. They went around the side path instead of that steep hill. It was about 2 p.m. when that heavy casket was carried up the knoll." The Commodore's pallbearers were John, Wesley and Oscar Mitchell, a Youngblood and a couple of other men who names have faded with time. After the casket reached the top of the knoll, refreshments were served, followed by the burial and his casket being lowered into the ground by six men holding ropes. When the casket reached the bottom, the ropes were removed and the first shovelfuls of earth were scooped onto the casket. Then a layer of flowers was added, followed with more dirt and more flowers. A distinguished citizen of Soledad had been laid to rest. He was buried beside his wife, Ellen, born Dec. 17, 1848 — the woman who delivered his family from Missouri. She had been buried in the same Mitchell-Dyer Cemetery on one hot July day (July 9, 1906), long before Francis was born. Francis Jansen was 9 when her grandfather was interred.

On a warm autumn afternoon, Commodore Perry Dyer's grandson and namesake, William "Perry" Dyer, died in Palm Desert. The date was Sept. 28, 1998. Perry Dyer distinguished himself as a Coachella Valley farmer and beekeeper. At one time in Perry Dyer's life, he was the nation's largest honey producer and even served as president of the Sue Bee Honey Association. This family man carried out a traditional work ethic, and like several of his cousins, he was also a community man who served as president of the Yorba Linda School Board as well as elder and chairman of the board of the Coachella Valley Christian Church. Perry Dyer served as ranch manager of Marshburn Farms for more than three decades. At the time of his death in semi-retirement, he was manager of the Growers Gin and a partner in the Oasis Desert Sun Ranch. Francis wanted to be there but was too ill to attend her brother's funeral that day. Just two days later, on Sept. 30, another of the Commodore's grandsons, Jim Dyer, succumbed to the Alzheimer's disease that had been eating away at him for a number of years. At 67, Jim Dyer was J.T. Dyer's last living child, a local valley beekeeper who had been in business with his brother, Willis, in the 1950s. Willis and Frank helped to construct the original Dyer's Honey House at the corner of Agua Dulce Canyon road and Escondido Canyon road. When it was built, the Agua Dulce Honey House, Jim Dyer was just a kid. As the brothers outgrew their business together, Jim took over the honey house quarters. When Jim was a teenager and still in school, his father gave him 50 beehives to get a start in the family business. Today the Agua Dulce Honey House is owned and run by Jim's son, Brian Dyer, who maintains the family's honey business. After the brothers separated their business, in the 1950s Willis Dyer went on to build a new honey house on Sierra Highway near the Canyon Country Little League Baseball field. For a time, the Sierra Highway Honey House was owned and run by both Frank and Willis. Eventually, Willis took over the Sierra Highway location on his own. When Willis retired, he sold his honey house business to the Warmuth family, which keeps the beekeeping tradition alive at the locale on Sierra Highway. Jim Dyer was the Commodore's last remaining grandson. What hardships were braved, we might never comprehend, but they led to a dynasty that continues today. Although both the Commodore and his wife, Ellen, have long passed, Canyon Country and surrounding communities are richer for their early contributions. Their extraordinary immigration from Missouri and their life experiences weave a common thread among their descendants, not just genetically but also through the lessons of character and hard work. The Dyer family continues to know preeminence in the beekeeping industry throughout the western United States and indeed the world.

|

SEE ALSO:

Story: 20th Century Vasquez Rocks

Commodore Perry Dyer, Soledad Pioneer (Story)

Brochure ~1930s

1930s Claude Ellis Art x5

Feature: Willis Dyer

James Thomas Dyer

1881-1960

Points of Interest w/ Letty Dyer Foote

Legacy: Dyer Family

"Werewolf of London" 1935

The Ivory-Handled Gun 1935 (Full Movie+)

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.