|

|

|

SCV NEWSMAKERS OF THE WEEK:

Joe Cassmassi

Planning and Rules Manager

Sam Atwood

Media Office Manager

South Coast Air Quality Management District

Interview by Leon Worden

Signal Multimedia Editor

Sunday, September 11, 2005

(Television interview conducted Aug. 30, 2005)

|

Joe Cassmassi

|

|

"Newsmaker of the Week" is presented by the SCV Press Club and Comcast, and hosted by Signal Multimedia Editor Leon Worden. The program premieres every Wednesday at 9:30 p.m. on SCVTV Channel 20, repeating Sundays at 8:30 a.m.

This week's newsmakers are Joe Cassmassi, planning and rules manager, and Sam Atwood, Media Office manager, for the South Coast Air Quality Management District (AQMD). Questions are paraphrased and some answers may be abbreviated for length.

Signal: Joe, you're the planning and rules manager for AQMD?

Cassmassi: One of them, yes.

Signal: Your background is in meteorology.

Cassmassi: Yes.

Signal: Is it true that Santa Clarita Valley has some of the poorest air quality in the entire nation?

Cassmassi: Unfortunately, using the statistics that we use, yes it is. The levels of ozone — which is a form of oxygen, but is a pollutant — have been recorded to be fairly high in the Santa Clarita Valley. It has a relatively high frequency.

Signal: Back in the 1970s, the air looked a lot blacker in the L.A. basin than it does now. If it's so bad, why does it appear cleaner now than it used to?

Cassmassi: Actually it is a lot cleaner. All you have to do is go back — 20 years ago there were 100 days during the year when we had Stage 1 alerts in the South Coast Air Basin, and that includes Santa Clarita (and) the non-desert portions of Los Angeles and Riverside and San Bernardino counties and Orange County. The last few years, we've seen virtually no Stage 1 episodes in this air basin. We've had a remarkable program of cleaning the air.

Unfortunately, we still have a lot of smog left there. One of the pollutants that contributes to that black haze, or the dark horizon, you might say, are fine particulates. Those levels, as well as ozone levels, have come down significantly over the last two decades. And if you went even further back, even more so as we go back in time.

Signal: How much of the bad stuff in the air is actually generated within the Santa Clarita Valley, and how much of it blows up here from down below?

Cassmassi: We did an analysis to take a look at that problem specifically, and we found that you get — about 9 percent of the smog comes from the Ventura and the Santa Barbara areas. But the overwhelming majority of it, at least 90 percent of it, will come from the San Fernando Valley and Los Angeles County as the wind blows onshore and through the Santa Clarita area.

So when you do the mathematics, you're looking at 1 to 2 percent of the actual smog that occurs here is pretty much generated here. A lot of it is "resident," or carried over from the pervious day, and so you start from a platform that's a little bit higher and then the "transport" of smog, actually carried by the wind, contributes to the daily pollution levels we see.

Signal: What exactly is the South Coast Air Quality Management District, and what is its responsibility in terms of making our air cleaner?

|

Sam Atwood

|

|

Atwood: We're a regional government agency responsible for cleaning up air quality to meet federal and state health standards. We have a very large jurisdiction across four counties, more than 10,000 square miles, which includes most of L.A. County — minus the High Desert and the Antelope Valley — all of Orange County and the San Bernardino Valley and mountains, and most of Riverside County. So it's a huge jurisdiction.

Our responsibility is to develop air quality plans that map out the overall strategy for how we're going to clean the air, and how our partner agencies are going to help us clean the air, and then to implement those strategies to the extent that our authority allows us to do so.

Signal: If only 1 or 2 percent of the bad things in our air are generated here, what is AQMD doing to control the emissions from the places most of it is coming from?

Atwood: We've had a host of air quality control programs for over 50 years, going to our predecessor agencies. Our primary area of authority has to do with the businesses and the industries, the so-called "stationary sources," of which we regulate more than 26,000. So we have all kinds of regulations that govern everything from the corner gas station and dry cleaner all the way up to the oil refineries and the power plants.

Now that we have controlled many of those sources to a fairly high degree, we're starting to look at other sources of air pollution such as locomotives, such as the ports, which we traditionally have not regulated, and for which most of the authority lies with the state and federal government. But we're trying to push the envelope to see what we can do with those sources of air pollution, as well.

Signal: You're talking about regulating cargo vessels, or things that are coming in on the vessels?

Atwood: The cargo vessels themselves. The ships at the port. The ocean-going ships are a huge source of air pollution. We're trying to both work with the federal and state government as well as the "No Net Increase" Task Force that the former (Los Angeles) Mayor Hahn instituted, to see what can be done to at least hold the emissions at a steady level and not have them increase with the huge increase in trade that has been happening over the past many years.

Signal: Those words, "no net increase" — when you look at environmental impact reports from new housing projects, you invariably see that our valley is a "zero attainment area." What does it mean to be a zero attainment area?

Cassmassi: When we're talking about no net increase, per se, what we're trying to do is see growth occur without having a negative impact to the air quality. We're trying to make certain that measures are taken by the sources of emissions, such that you do not essentially increase your "emissions inventory," or the amount of pollution that comes into the air so that air well degrade.

In areas such as the Santa Clarita Valley, for example, growth will have mitigation measures to try and mitigate traffic that might be caused by additional housing. It may require such measures as to instigate traffic-flow regulations, possibly rideshare programs — many, many different small programs added together to essentially try and offset the gross emissions that go into the atmosphere during the development and after the development of a project.

Signal: Isn't it the case that any increase in growth will necessarily increase the amount of smog? You can't build a house without using a tractor that's going to belch out something bad.

Cassmassi: I think the careful thing to look at is, when we look at the trends of air quality — we've improved air quality to the tune of 50 or 60 percent over the last couple of decades. In that same time frame, the population of Southern California has escalated at a alarming rate. We're looking at now 15 million to 17 million people in Southern California and in the L.A. basin, whereas years ago, there wasn't anywhere near that number of people.

The other thing, too, is, we have more cars on the road. Cars are roughly 70 percent of the problem for smog. When you talk about what is Santa Clarita's contribution, there is pass-through traffic that comes through the community which does have sometimes a negative impact, and ironically, sometimes a positive impact on air quality.

Signal: How is that?

|

There are fewer Stage 1 smog alerts today than there were 20 years ago.

|

|

Cassmassi: Well, the emissions that come out of tailpipes sometimes gobble up some of the ozone that's being formed. It's sort of a ironic situation. When those cars aren't there, sometimes we see a little bit more smog, due to the fact that more smog is being transported.

Signal: Never heard of cars on the freeway being good for air quality.

Cassmassi: Well, it depends on where they are. Unfortunately for Santa Clarita and many of the downwind communities, even to the east of the Los Angeles basin, it's really an issue of numbers of cars. You have 15 million people, 10 million cars on the road. There's quite a bit of potential to actually form smog on any given day.

Signal: What's better for the air, gasoline or diesel?

Cassmassi: That's a good question. Diesel particulates that come out of diesel sources are considered to be carcinogenic, and so direct respiration of diesel soot is not beneficial to the population.

Diesel engines, however, tend to produce a little bit less pollution in terms of hydrocarbons — that's sort of like the gasoline derivatives — and they're considered to be more fuel efficient. The flip side of the coin is, automobiles tend to produce less toxics, but they produce more of the building blocks of smog. There are a lot more cars on the road right now than trucks with diesel, but we still note that diesel is a big contributor to the smog problem, from the standpoint both of diesel particulate and some of the components that do come out of their exhaust.

Atwood: We've had an active program and a set of rules for the past several years that have moved a lot of the fleets — for example, transit buses, street sweepers, trash trucks and school buses, even — from diesel toward alternative fuels.

The reason is, as Joe is mentioning, is that diesel fuel-burning engines create a lot of toxic diesel soot and a lot of nitrogen oxides as a building block to smog, and fine particulates. So while diesel, as Joe mentioned, is more efficient and perhaps offer lower greenhouse gas omissions, they do have more smog and toxic-forming gases in most cases.

Signal: Some of the regulations you've mentioned are probably some of the very ones business owners complain are too onerous. How much of the price of a gallon of California's "cleaner burning" gasoline can be attributed to measures that have been taken to improve air quality?

Atwood: I think it's a relatively small piece of the pie, especially when you consider the price of gas today. The California Air Resources Board in Sacramento is the agency that sets the fuel specifications and standards, and each time they adopt a regulation to make gasoline cleaner, they do a thorough economic analysis including that very question of how much is it going to cost the consumer at the pump?

They have done a couple of major phases of reformatting and cleaning California gasoline. I think in each case, the answer has been about perhaps a nickel a gallon, or something to that —

Cassmassi: Somewhere in that neighborhood. And again, (with) market prices, it's very difficult to assess. You go to one part of the community, it's going to be a little higher than the other.

Atwood: Another thing to keep in mind is the benefits to, for example, cleaning up gasoline or cleaning up the air through other measures. The benefits are cleaner air (and) improved public health.

So for example when we do our air quality management plan, and we revise it every three years or so, we look what the cost will be, and we will look at what the benefits will be. In each case, the benefits outweigh the cost.

The benefits would be reduced premature deaths due to the reduction in particulate matter; reduced number of trips to the emergency room; reduced hospital admissions; reduced absenteeism at school and at work, those sorts of things.

There are things that perhaps the business community might have a little tougher time grasping, but they are qualifiable costs, and when you consider the overall net effect on society, the overall economic effect is beneficial.

Signal: The growth projections for the Santa Clarita Valley are staggering. The population of the SCV and Antelope Valley should climb from a combined 550,000 today to 1.2 million in 20 years. When you talk about "zero net increase," is there even a way to keep up? Are there things on the horizon that will make a significant difference that fast?

Cassmassi: We have technology assessment office that's looking all the time at new technologies, be it either hydrogen automobiles — they were pioneers with fuel cell development — non-hydrocarbon-based coatings, water-soluble coatings — a lot of these technologies are technologies that were born out of years of development.

We're given enough time to try and compensate for the eventual attainment of the standards, or to meet the clean air standards, because the government realizes — and this would be EPA, as well as the California Air Resources Board realizes — that we need time to develop these technologies. A lot of funds are being expended to try and develop the new types of technologies.

We're also looking at having our partners in this — EPA and the state — provide us with additional control measures, additional controls that will take care of the sources that we really can't touch. Those are the interstate sources, the international sources of pollution, which eventually come and play a role.

Now, in terms of a community like Santa Clarita, there are mitigation measures that can be taken in the short term to keep air pollution down. For example, if you're doing construction, you can water, you can use soil stabilizers, you can use "best engineering practices," and that actually helps not only in the short term, but (also) in the long term.

One of the goals of the whole air quality plan is to attain the standards despite growth. So it's going to be a test that we'll be looking at beginning this year and carrying us through to 2007, when we have to go to the EPA with a new state implementation plan, which would include all the potential measures that would help bring us into attainment down the road for both ozone and fine particles.

Signal: Give us your assessment of how well the city of Santa Clarita is doing to address air quality.

Cassmassi: My dealings with the city, in terms of their air quality element, which is part of their General Plan — they've been very aggressive. They've started alternate-fuel refueling stations; they've looked at coordination of traffic; they have looked at rideshare programs; these are the level of programs that really address the residents of Santa Clarita, many of whom commute to and from the city to go to work, and in some cases to Santa Clarita to do their jobs.

It's this type of an aggressive program at the city level that really stands out as a classic example for the rest of the cities in the basin. They have been very aggressive and seek to employ more and more measures that will help clean up the area.

Signal: Are there things you'd like to see the city or county do that they're not doing?

Atwood: There's nothing that I'm aware of. I would just reiterate what Joe has said — that the city of Santa Clarita has adopted a model air quality element, which is very important to do.

AQMD has recently developed a guidance document for cities and counties to help them in just what you were talking about, in terms of planning local development. It basically gives them a tool to use, to help them be aware of the air quality impacts of developing new housing projects, new roads and that sort of thing. AQMD doesn't have any local land-use authority, but we try to serve as a technical advisor, as a resource for cities, to help them when they're planning big projects.

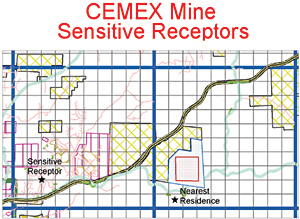

Signal: The city of Santa Clarita and numerous local organizations are upset about Cemex's plan to extract 78 million ton of sand and gravel from Soledad Canyon over a 20-year period. One big concern is the potential impact on air quality. How much "stuff" will be thrown into the air, and how harmful is it?

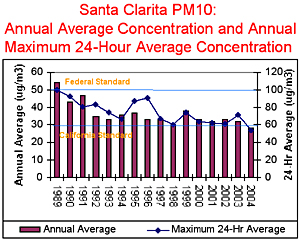

Cassmassi: We've taken some basic analysis of the Cemex project as it is planned, in the environmental impact report, and the actual mining activities will increase some of the particles in the air, the dust. It will not really cause a violation of the federal standard. It may contribute to a violation of the state standard, because the city of Santa Clarita is hovering right around that standard level right now.

We also looked at the potential impact from the diesel machinery that would be used in the mine, and potentially from some of the hauling that may occur. A vast majority of that will be down (Highway) 14 and Soledad Canyon Road, and there will be a little bit of an impact. There will be increased risk to the community. But right now it's at a level that we have calculated that should be within the tolerance of what we call our AB 2588 Rule, which essentially requires notification at specific risk levels. This would require notification.

Signal: To whom? The people within a certain —

Cassmassi: To the people that would be within the community along the transit routes, as well as adjacent to the mine facility.

|

The planned Cemex mining might violate state tolerances for emissions but shouldn't exceed the federal standard, AQMD officials say.

|

|

Signal: There's an elementary school fairly close to the mining project. Are kids more at risk than the general population?

Cassmassi: Usually when we think of the sensitive population, kids are always at risk for air pollution. Because, one, their lungs are developing, and No. 2, they're outdoors quite a bit and running around. When you're running around you tend to respire, or breathe in, nine times more than a person that is sitting down doing a passive activity. So kids definitely are always at risk more.

When we did our analysis, we found that the impacts to the sensitive receptors would be, again, below that 10-in-a-million risk factor, which is what we call the AB 2588 notification level.

Signal: The city of Santa Clarita would probably like to see the AQMD come out and say the Cemex project is a bad idea, but it doesn't sound like that is going to happen.

Atwood: Well, again, our role in these kinds of projects would be to review the environmental impact reports and to comment on them in terms of their technical adequacy, and also to take a very close look at the mitigation measures proposed.

We have and we will be taking a very hard look at the mitigation measures proposed, and if we feel they're not adequate, we will strongly suggest that some stronger measures be put in place.

We've done this in other cases, for example down in the ports, with some of the pier expansion programs proposed there. And in the city of Long Beach, a major project there is taking probably a additional year to step back and look at some more mitigations as a result of the comments that we made there.

Signal: Didn't the AQMD issue some kind of a position paper on the Cemex project a couple of years ago, outlining the agency's concerns?

Cassmassi: I believe you are correct. I believe there was a comment on the draft plan. Unfortunately I'm not familiar with what was in that letter. I just do know that there was something that was responded to on that.

Signal: Were there some areas of concern before that aren't areas of concern today?

Atwood: We're continuing to be taking a close look at the plans for the mine as they develop, and in addition, any equipment at the mine which requires an AQMD permit — that is something that we do have jurisdiction over. So if it's, for example, a fixed engine that would be used to power equipment, or crushing equipment — those are the kinds of things that would require an AQMD permit. We could place permit conditions to ensure that any dust or emissions are minimized, and we could also send inspectors on an unannounced basis to make sure those conditions are being met.

Signal: So AQMD has a formal, ongoing monitoring role? What is AQMD's monitoring responsibility in general?

Atwood: Each of the facilities are required to submit emissions estimates each year, and we have compliance personnel.

Signal: Does that include any manufacturer?

Cassmassi: (Yes.) Anyone who has equipment that is permitted by the AQMD will submit emissions estimates and have permits issued. We have compliance personnel that go out on a routine basis, and then if there are complaints, they will go out and issue notices of violation if they find that the operator is not working within the aspects of their permits. So there's an active program ongoing that is actually looking at not only the mining activities, but the activities of all the (pollution) sources in the basin.

Atwood: We have over 100 field inspectors who go out to these 26,000-plus businesses, and of course they tend to focus on some of the larger sources, which may represent some of the greatest sources of emissions, like an oil refinery. But they also go to service stations, dry cleaners, auto body shops, the kind of commercial facilities you find in neighborhoods.

They make unannounced visits. When they find a violation they can issue a notice of violation, and that's then taken to AQMD's district prosecutor, where we will attempt to settle the violation with the violator. If we cannot reach a settlement, we can and we do take violators to court to seek a civil penalty.

Signal: Where in the Santa Clarita Valley is the air quality measured, and is the air better in one part of the valley than another?

|

The onshore flow carries ozone toward Canyon Country, leaving the air over the western and northern portions of the valley a little cleaner.

|

|

Cassmassi: Right now the air monitoring station sits off of San Fernando Road, pretty much dead-center in the middle of Santa Clarita.

As it turns out, there is a difference. If you go to the western portion of the city, it tends to be a little bit cleaner, simply because the wind is blowing up the Santa Clara River Valley, and that wind usually comes up from the Ventura-Santa Barbara area, which tends to be a little less polluted. So the western portion of the city right now, and the northern portion of the city, tends to be a little bit cleaner.

Signal: Great. Folks on the east side of town always say everything good happens on the west side of town, and now the west side has the better air, too. As we wrap up, what do you want people to know? Stop driving Hummers?

Atwood: The air is getting cleaner. It's going to continue to get cleaner. Certainly there are things that people can do to help that process. AQMD has a Web site, cleanairchoices.org, that will let you know what are some of the cleanest vehicles you can buy, if you happen to be in the market for buying a new vehicle.

But we're headed in the right direction. It's going to be a difficult challenge to achieve clean air, and we are going to need the help of all the residents of Santa Clarita and throughout Southern California.

See this interview in its entirety today at 8:30 a.m., and watch for another "Newsmaker of the Week" on Wednesday at 9:30 p.m. on SCVTV Channel 20, available to Comcast and Time Warner Cable subscribers throughout the Santa Clarita Valley.

©2005 SCVTV.

|

|

|