Did a naughty teenager make the six 1943-S bronze cents?

By Leon Worden

June 2006

| C |

The jury is out on the first two questions. But now, after more than 60 years, comes a compelling tale that, if true, could unravel one part of the mystery of the 1943 bronze cent.

Understand, 1943 bronze cents have been the rage ever since 16-year-old Don Lutes Jr. found one in change from his school cafeteria in 1947. The popularity of the off-metal errors quickly transcended the collecting community. Newspaper and matchbook-cover ads offering a huge "REWARD!" compelled a generation of Americans to rifle their purses and pockets for the elusive treasure.

More than a few people have walked into a local coin shop with dollar signs in their eyeballs, only to learn their great find was a cheap fake. (Tip: Use a household magnet. If it attracts, it's a copper-coated steel forgery. If it doesn't, take it to a knowledgeable dealer. Chances are, it's still phony.)

But like Willy Wonka's gold certificate finders, there were some winners. Today, most certified 1943 "coppers" trade in the neighborhood of $100,000. In 2003, a unique specimen with a "D" mint mark sold at auction for a whopping $212,750 — more than 20 million times its original issue price.

According to Dr. Sol Taylor, author of "The Standard Guide to the Lincoln Cent," and Steve Benson, who has investigated every bronze 1943 cent and once owned the finest "P" and "S" examples, there are 13 known specimens from the Philadelphia Mint, six from San Francisco and one from Denver. Almost all were found in circulation, and their raison d'etre is, at best, educated guesswork.

Were some bronze blanks left in the hoppers at the end of 1942 and carelessly commingled with their zinc-coated steel replacements? Were they lodged in the feeding chutes of the coin presses and pushed through unnoticed when the dies were switched out for the new year?

It would appear, based on a review of the literature and discussions with experts, that in all the years, no one has stepped forward with direct knowledge of the fabrication of these numismatic anomalies.

Until now.

"The superintendent only let high school students work on the penny and nickel presses, apparently because he didn't trust them with higher-value coins," Reis writes. "My father was assigned to work on the penny presses."

"My father said that one day, he came across a 'handful' of copper penny [sic] planchets. I never asked him exactly where he found them. He said that he didn't tell anyone that he found them and that he threw them in with the steel planchets being fed into the penny presses. He said he retrieved five or six of the copper pennies and brought them home to give to his mother."

Reis (pronounced "Reece") said his father first told him the story in 1960 when he was 10. He immediately asked his grandmother to hunt for the coins, but "she had no memory of my father giving her any pennies ... 17 years earlier." He said that that over the years his grandparents told him similar stories of his father's wartime escapades at the Mint.

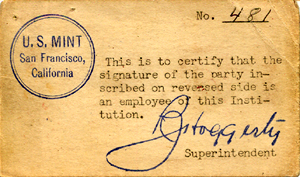

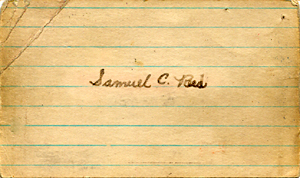

Reis disclosed the information by e-mail to Sol Taylor in February and produced a copy of his father's San Francisco Mint employee card. Undated, it is signed by Peter J. Haggerty, superintendent of the Mint from 1933 to Dec. 31, 1944. Handwriting on the back (perhaps penned by a clerk) juxtaposes the first and second names of Reis' father — Charles Samuel Reis Jr. — as "Samuel C. Reis." The card identifies him as employee No. 481.

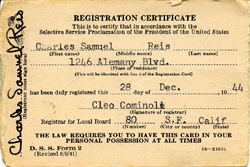

He also sent Taylor a copy of his father's Selective Service registration certificate, dated Dec. 28, 1944 — his 18th birthday.

Reis' father died March 2, 2005, aged 78 years. His father's sister died a month later. She had been executrix of their parents' estate. Reis found his father's Mint employee card among in a box from his grandparents' estate. He didn't find any coins.

Reis contacted Taylor through the Web site, soltaylor.com, and asked Taylor to give his "estimation of the credibility of these stories."

"[Finding] my father's mint card was sort of a trigger," Reis told COINage. "Not that I had forgotten [the stories] or anything. I was just wondering if there's any way to confirm them from another source. For me, I think it would be really neat."

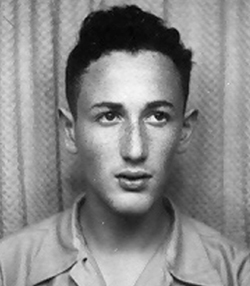

Born in 1926, Charles Reis grew up on Alemany Boulevard in San Francisco, where his parents lived since 1920. After his temporary Mint job, Charles, who developed an interest in engineering at Balboa High School, worked for the U.S. State Department as an engineer on Voice of America radio broadcasts. Around 1950 — when David was born — he went to work for Hewlett Packard, which was making high-speed frequency counters for radio stations and, later, oscilloscopes. By 1966 or 1967, Charles had saved enough money to retire and buy an apartment building, which he converted to condos.

"My father never said to keep [the coins] a secret," David Reis said. "I guess I just didn't think anybody would be so interested in it. But since he passed away, it's just one of those things. You kind of feel an obligation to pass that kind of history on, if it is of interest."

Taylor's verdict?

"I believed everything that he said is accurate."

Taylor knew that many Mint employees were drafted into military service and yet somehow, the coining facilities managed to operate at or near capacity during the war.

Taylor said Reis' story explains why no 1943-S bronze cent was known to exist before the first one was discovered in 1973. In contrast, every known P-mint coin had been pulled from circulation by 1960, Taylor said.

"Why didn't this coin show up between 1943 and 1973? Because all of them were in the possession of one family," Taylor said. At some point, a family member "probably found some loose change and spent them. And then they started showing up."

"The 1943 copper is probably the best known of the Lincoln cents," said Taylor, who has collected Lincoln cents since the late 1930s and handled them professionally since 1953. "There were probably 10 million people looking for it, and if they were in circulation for 30 years, somebody would have found one or two."

Collector-researcher Steve Benson doesn't think the known S-mint coins were stashed away for 30 years because they're too worn. Four of the six are listed in Taylor's book as EF-40, one as EF-45 and one as AU-50.

"If they were in one person's hands, they'd probably be in tremendous condition," Benson said.

Splitting the difference, if Reis' grandmother had no recollection of the coins in 1960, she might have unwittingly released them into circulation in 1952 or 1953 when she moved from San Francisco to nearby San Bruno.

"They condensed their belongings, I guess," Reis said. "When you move you condense them. You get rid of things."

The coins' circulating time would have been cut by a decade. Their condition is still relatively high for coins that have been used in commerce — and the AU-50 coin was subsequently regraded MS-61 by Numismatic Guaranty Corp., Benson said.

"Let's assume they were spent after 1953," Taylor said. "The Philadelphias weren't discovered right away, either."

Circulating since 1943, the first Philadelphia coin was detected in 1947. The next discovery to receive wide publicity came in 1958. Another was reported in 1960.

"In any event [the San Francisco coins] weren't out there too long," Taylor said. "If they were circulating since 1943, there would be some VFs," showing more wear. There aren't.

Current U.S. Mint personnel said no documentation exists to confirm whether teenagers were hired during World War II.

"I never heard such a story and imagine it is anecdotal," said prominent numismatic author Q. David Bowers. Researcher Robert W. Julian, a walking database of old Mint records, said it is "possible thatša teenager worked at San Francisco, as there was a severe labor shortage during the war." But it probably would have been light work such as janitorial service, he said.

"It's kind of difficult to think that they would hire 16- or 18-year-old kids to handle that kind of equipment," said error coin specialist Fred Weinberg, who in 35 years has handled several bronze 1943's. "Even back then, those presses were big, heavy and could have been considered dangerous. They would have done better to hire somebody in their 50s or 60s. But if he says he ran the presses, I guess he ran the presses. If he has a Mint employee ID of some type, that lends some kind of credence."

There are several theories to the 1943 bronze cent conundrum. You can add the "naughty teenager" theory to the list — although it's not the first to call into question the diligence of temporary Mint employees.

"Because of the war, the Mint had trouble getting competent help," the late numismatic researcher John J. Ford Jr. told COINage Senior Editor Ed Reiter in an interview. "So the quality control was not as good as usual at the time. A lot of copper cents were caught, I assume, but others got by and proceeded to enter circulation."

Ford said that in the early 1940s, "the planchet-feeding mechanism for one-cent pieces consisted of galvanized chutes with straps. Presumably, some of the bronze planchets got hung up in the straps in December 1942." Then, "when the steel blanks came along in early 1943, they pushed the bronze pieces along and they, too, were struck."

This "stuck in the press" theory is disputed.

"That's not the way it works," said Taylor. "The planchets are produced by cookie-cutter machines and then dumped into hoppers which look like coal carts, which can hold up to a million planchets. I was at the Denver Mint in 1976 and I saw these carts, which had been in use since 1906. When you tip them over, all the coins slide out. I noticed when they emptied the cart and then they sent it back to the planchet room, there were a couple of sticky planchets — planchets still stuck in the cart."

"The most widely held theory is that the 13 [Philadelphia] pieces were stray 1942 planchets that never got out of the hopper until they were mixed in with the steel planchets," Taylor said. "When they were dumped, they wound up in the production line. They weren't stuck in the presses. It was further back in the minting process."

Weinberg concurs. "I don't believe they were in the machine. They were in a tote box, they were in the wrong place, they were on the floor. Somebody picked them up and threw them someplace and they ended up getting fed into the press. But they weren't sitting in the chute or the feeder fingers or the collar, in my opinion. When you pulled out the 1942 dies and put in the 1943 dies, you'd see any planchets that were sitting in the coining chamber or the collar."

Slipups weren't unique to the 1940s, and they haven't always involved blank planchets.

"There are Sacagawea dollars struck on struck state quarters," Weinberg said. "There are 1999 pennies that have been struck on 1998 previously struck dimes. So obviously that 1998 dime was stuck in the tote bin [or] it was on the floor and was thrown in the wrong bin. It does happen. That's the bottom line."

If Reis' account is correct, the San Francisco coins weren't made by accident, and they weren't made at the beginning of the year.

"My father had a summer job," Reis said. "It was in the middle of the year."

When were the Philadelphia coins made? "Because they were discovered in different places at different times," over a period of 13 years, "it was not the work of one person having fun at night," said Taylor.

One person who did have fun in Philadelphia was John Sinnock, then-chief engraver of the Mint. Although it appears he never confessed the way the Reis family has done, Sinnock is thought to have made many dark-of-night oddities for friends, including one 1943 bronze cent that he gave to a special lady friend in upstate New York.

Sinnock is also credited with the coin's corollary — a 1944 cent on a steel planchet. The planchet could have been left over from 1943, or it could have been a blank intended for a 1944 Belgian 2-franc coin made by Uncle Sam, Weinberg said. The planchets were identical.

Benson said another 1943 bronze cent from Philadelphia was given to a woman in Boston by the Philadelphia Mint superintendent.

One popular test of authenticity for 1943 bronze cents assumes they were made on a standard production press. "Any such genuine coin, having been struck under a pressure intended for steel, will have its edges built up like the most perfect proof. From the standpoint of visual detection this is the most crucial test," Don Taxay wrote in his landmark 1963 book, "Counterfeit, Mis-struck and Unofficial U.S. Coins."

The rule should apply for the S-mint coins if Charles Reis made them. But Benson says it doesn't always work with P's.

"Of the 13 [Philadelphia] specimens that I have pictures of, there is some repeated diagnostic weakness on the obverse and corresponding diagnostic weakness on the reverse," he said. "The question is, why would this coin show any weakness [if the] press is set up to strike steel planchets? The detail should be extraordinarily great. But of the 13 specimens, at least six or eight have this weakness."

Benson believes these coins were struck deliberately on an unused press in some other area of the Philadelphia Mint, away from watchful eyes on the production line.

This corresponds with the "locker room" theory, which involves rumors that an employee stamped the coins somewhere else in the Philadelphia Mint and got caught when his locker was raided.

"But then there are some other Phillies that are extraordinarily sharply struck," Benson said. "Those are the ones that are struck on the production press."

"One summer day, the owner of a gas station that was across from the Mint came over to the Mint with a handful of nickel slugs — actually nickel planchets — that he retrieved from the Coke machine at his gas station," Reis wrote to Taylor.

Assuming some thirsty adolescents lifted a few coin blanks, "the superintendent immediately fired all the high school students that worked on the nickel presses. My father was not fired because he worked on the penny presses. [He was] perhaps the only student that worked on the penny presses."

Haggerty, the Mint superintendent, had been around awhile. According to Nancy Oliver and Richard Kelly, authors of "A Mighty Fortress: The Stories Behind the 2nd San Francisco Mint," Haggerty took charge of "The Granite Lady" on July 1, 1933, and he oversaw construction of the modern San Francisco Mint facility in 1936-37.

But even with a pistol range in the attic of the new building, it seems he didn't have a tight grip on the place. He didn't need fresh headaches — especially from teenagers.

"One evening last week," TIME magazine reported Jan. 9, 1939, "Paul Francis and William Gallagher, each 15, walked past the massive ... money fortress and remembered having read it was 'impregnable.' So Paul and William shinnied up a drainpipe to a window ledge."

It was a second-story job. They found an open window, walked past a guard reading a newspaper, found the "attack-proof steel doors" ajar and entered a room of bronze coin strip. They gathered an estimated $1.50 worth of scrap and left the way they came. They tossed their booty to the ground outside and called the cops on themselves, for bragging rights.

"I[t] was a breeze," they told TIME. "Like throwing an egg into an electric fan."

"A couple of Houdinis!" a sheepish Haggerty exclaimed.

Unwelcome as they might have been at the time, a few pesky teenagers could be helpful today. They could say for certain whether high school students filled in on San Francisco's coining presses during World War II, and if so, whether they decided to leave "quality control" to the grownups.

Hopefully, for Reis' peace of mind, the publication of his story will ferret out the corroboration he is seeking.

Then again, it might be best if no link between Charles Reis (or John Sinnock, for that matter) and the known 1943-S bronze cents is proved beyond a reasonable doubt. If 16-year-old Charles found a half-dozen bronze planchets inside the San Francisco Mint, tossed them into the coining press, clandestinely retrieved them and gave them to his mother, then they would not be "coins" in the strictest sense because the Treasury Department never issued them as legal tender. Instead they would be stolen government property — if only a few cents' worth of copper-tin-zinc alloy — and even now, they could be subject to seizure.

©2006, MILLER MAGAZINES INC./LEON WORDEN. RIGHTS RESERVED.

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

|