|

|

Keeler, California

|

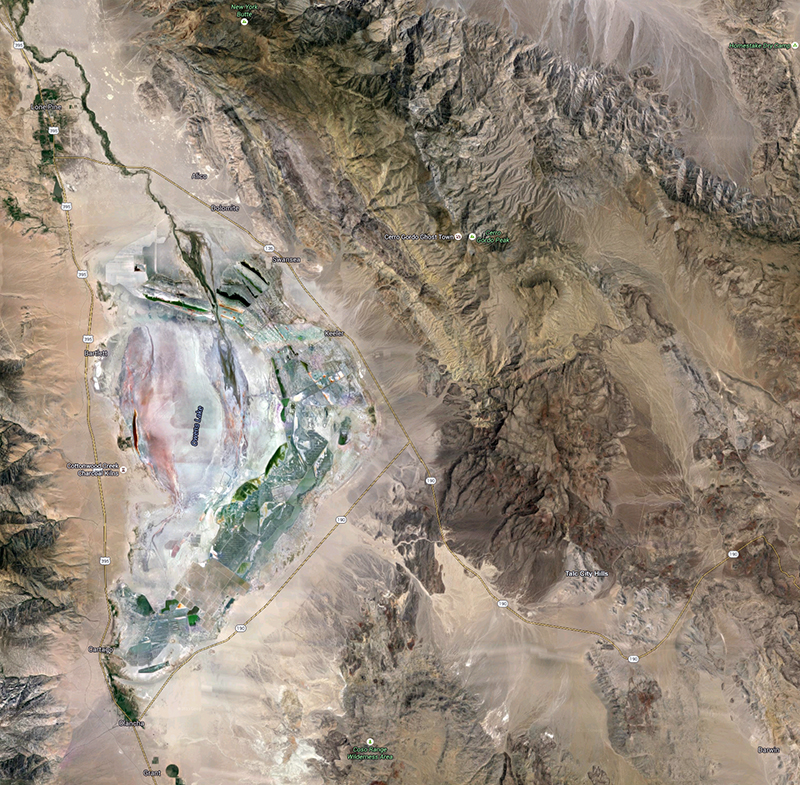

May 22, 2015 — Two major and unrelated milestones in the growth of Los Angeles — and a third development that impacted almost every early-20th-century American household — come together at tiny Keeler in Inyo County. Located on the former eastern shore of Owens Lake near the foot of the 8-mile-long Yellow Grade Road to the old silver and zinc mines of Cerro Gordo, Keeler isn't quite a ghost town. A few dozen people live there, including some who work on the L.A. Department of Water and Power's dust mitigation program.[1] We'll explain in a moment. First came the silver that flowed out of Cerro Gordo in the 1870s to Los Angeles. Hauled by Remi Nadeau's freighters through the Santa Clarita Valley — with stops at places like Lang, where Nadeau established a station in 1873, three years before the trains came through — the ore brought wealth to the sleepy pueblo. It paid for L.A.'s first multistory buildings and enriched people like Nadeau, who would erect L.A.'s first four-story structure, the Nadeau Hotel, a decade later. It no doubt helped that the major Cerro Gordo mine owner's brother, real-estate tycoon Prudent Beaudry, was mayor of Los Angeles (1874-1876) during Cerro Gordo's heyday. A quarter-century later another L.A. mayor, Fred Eaton (1898-1900), was setting his sights on the same area — not for precious metals, but for water. That's the second milestone. Long story short, in 1906 engineer William Mulholland was hired to build the L.A. Aqueduct. Eaton and Mulholland bought up the water rights and started draining Owens Lake in 1913. Worried about earthquakes and angry Owens Valley farmers who occasionally dynamited the aqueduct, they built reservoirs along the way — like the one in San Francisquito Canyon which famously failed in 1928 and killed an estimated 431 people. Today, the big pipes that transect the Santa Clarita Valley are the same pipes that carried L.A.'s Owens River water to the Cascades at Sylmar a century ago. (Now they also bring water from the Mono Basin.) Historic markers and ghostly relics dot the landscape in and around Keeler, some from its Cerro Gordo period, some from subsequent activity. Keeler was established after the 1872 Lone Pine Earthquake wiped out the pier at nearby Swansea (which has vanished, save for a few ruins). At first, the steamship Bessie Brady ferried ore across the lake from Keeler to the southwestern shore at Cartago, shaving off a bit of the transportation time and cost. (Imagine that — a steamer plying the waters of Owens Lake.) The Bessie Brady was destroyed by fire in 1882; in 1883 the Carson and Colorado Railway put in a narrow-gauge line with a depot at Keeler. The railroad eventually merged into the Southern Pacific. Apparently still in use today as a private home is the old Keeler schoolhouse, dating from the Cerro Gordo period. Silver and zinc production continued into the mid-20th Century — a smelter was built near Keeler in the first decade of the 1900s to refine zinc — but before long, as radios started to invade living rooms and wood-burning stoves gave way to ceramic models with heat-storing coils, another mineral came to the fore: talc. Southeast of Keeler off of Highway 190 to Death Valley are the Talc City Hills. There's no city there; Talc City was a steatite (soapstone) mining operation that was started in 1917-1918 by the Inyo Talc Co., which in 1922 changed its name to the Sierra Talc Co. Minerals from Talc City and other steatite mines that cropped up in the area, some even closer to Keeler, were trucked to the Sierra Talc Co. mill in Keeler where they were pulverized and loaded onto trains. According to Ben M. Page[2], as of 1951: During the first few years of operation, the [Talc City] mine provided raw material for insulating cores of Hotpoint stoves. The cores were turned out of block talc, which was then fired. It was later found that ground talc could be used for the same products, preventing great waste, and all the ore is now ground. Much talc from this mine has been sold to the paper, rubber, and cosmetic industries. However, manufacturers of electrical insulators for radio and other equipment began to draw upon the Talc City production about 1936, and by 1942 virtually the entire output was used in high-grade electrical ceramics. The mine is the largest producer of steatite in the United States, and prior to World War II it was almost the sole domestic source of radio ceramic steatite. Today, the abandoned Sierra Talc Co. mill at Keeler is the most prominent landmark in town. Talc wasn't the only non-precious mineral of value. Owens Lake is a dust bowl today, and the area surrounding Owens Lake was a dust bowl then — even before Eaton and Mulholland got their hands on it. Trona — sodium carbonate, used to make soda ash — was harvested from an area north of Keeler as early as 1887. Ponds were filled with lake water and allowed to evaporate over the summer, and then the trona was extracted and shipped to market on the narrow-gauge trains. In 1912, the Natural Soda Products Co. set up shop on the shore south of Keeler and, exercising mineral rights granted by the state, produced soda ash and other salines used in a variety of industries — glass making, paper, food additives, laundry products, medicine and more. As the formerly 108-square-mile Owens Lake dried up (by 1926), commercially valuable salts — sodium and potassium — were left behind. Expecting the dessicated lake to stay that way, Natural Soda Products Co. built a new plant in the lake to tap the brine.[3] But then a strange thing happened. In 1937, LADWP opened the valves and released Owens River water into the dry lakebed, partially flooding the soda plant. Natural Soda Products Co. sued and won. Los Angeles appealed to the state Supreme Court, but it upheld the ruling 5-1. The majority opinion[4] tells the story: In 1913, the defendant city of Los Angeles completed its aqueduct to the Owens River Valley and, from 1919 to 1937, diverted into it virtually all the flow of the Owens River, which formerly emptied into Owens Lake, a body of salt water without outlet. As a result the lake dried up and its subsurface became a crystalline cake impregnated with brines containing valuable chemicals. On the shores of the dry lake plaintiff had two plants to which brines pumped from wells on the bed of the lake were piped for the production of soda products. Plaintiff (Natural Soda Products Co.) acquired the older of the two plants in 1932, when it leased mineral rights in the lake from the State of California. Plaintiff subsequently extended its pipe lines several miles farther along the bed of the lake, drilled wells, and installed pumps and brine heaters, acquiring the necessary leases and rights of way from the state. The brines thus made available were of higher alkalinity and therefore of greater value than those previously obtained. To improve its efficiency in extracting chemicals from the brines so as to increase production, plaintiff built a new plant and adopted a new process. Plaintiff's operations were possible because of the dehydrated state of the lake bed, the continuation of which depended on the absence of any substantial flow of water from Owens River into the lake. The extent of the flow was determined by the manner in which defendant operated its aqueduct. Its dam across Owens Valley, forming Tinnemaha Reservoir, served to regulate the flow of the river. Below the dam, the water, which flowed through its natural channel until it reached Intake, could be directed into the aqueduct proper by means of defendant's diversion dam, or into Owens Lake if the gates in the dam were opened. On February 6, 1937, before plaintiff's new plant could be put into operation, defendant opened the gates at Intake, thereby causing a large amount of water to flow into the lake. Defendant continued to direct the water into the lake intermittently until July 1, 1937, and the surface of the lake became flooded to a depth of three or four feet. Natural Soda Products Co. was awarded $153,578.85 in damages in 1937 — and another $288,851.29 when LADWP did it again in 1938.[5] The high court affirmed that Los Angeles officials "had, by their long continued diversion of water from Owens River, obligated themselves to continue that diversion within the reasonable capacity of their aqueduct system for the benefit of plaintiff." Moreover, expert witnesses testified that it was "poor engineering practice on (L.A.'s) part to spill water into the Owens Lake" during the period in question. The court affirmed the soda company's assertion that excess water could have been "spread onto two lower spreading grounds, or spilled into the Los Angeles or Santa Clara Rivers." Finally a word about those dust mitigation workers. As federal air quality standards tightened in the 1990s and state regulators set new targets for the early 2000s, LADWP had a problem with the dust bowl it created. Periodic winds whipped up "a toxic cocktail of arsenic, cadmium, nickel and sulfates" (to quote the nonprofit environmental group, Owens Valley Committee[6]) — up to 4 million tons annually — threatening the public health in Keeler and beyond. In addition, historically the lake was an important stopover for migratory birds.[7] So, under a 1999 Memorandum of Agreement with the Great Basin Unified Air Pollution Control District, LADWP in 2001 launched the largest dust-control project in U.S. history.[8] It entailed, among other things, a reduction in overall pumping from the Owens Valley, and shallow flooding of a portion of the lakebed. Additional regulatory actions followed; today, LADWP spreads up to 95,000 acre-feet of water annually across 42 square miles of lakebed at a cost-to-date (2014) of $1.2 billion[9]. Dust levels still exceed state standards, but they've dropped by roughly 90 percent since 2001[10], and recharging the lakebed has created a marshland that supports more than 241 species of birds, including some that are federally threatened or endangered.[11] That's why portions of the otherwise dry lake look green today. — Leon Worden 2015 Further Reading: "Geology of the Cerro Gordo Mining District, Inyo County, California," by C.W. Merriam. Geological Survey Professional Paper 408, prepared in cooperation with the State of California Department of Natural Resources — Division of Mines. U.S. Department of the Interior: Washington, D.C., 1963.

1. Wasson, Sam (LADWP Ret.). "Track 15" on the website, "There it is — take it: Owens Valley and the Los Angeles Aqueduct, 1913-2013." [Link]

2. Page, Ben M. "Talc Deposits of Steatite Grade, Inyo County, California." Calif. Division of Mines: Special Report 8, August 1951. [Link]

3. Robertson, G. Ross (UCLA). "California Desert Soda: Plant of the Natural Soda Products Company at Keeler, Calif., on Owens Lake." Industrial & Engineering Chemistry, Vol. 23 No. 5, pp. 478-481, 1931. [Link]

4. Natural Soda Prod. Co. v. City of L.A., 23 Cal.2d 193 (L.A. No. 18066. In Bank. Nov. 4, 1943). [Link]

5. Natural Soda Products Co. v. City of L.A. (Civ. No. 14700. First Dist., Div. Two. Feb. 26, 1952). [Link]

7. Prather, Mike. "Track 14" on the website, "There it is — take it: Owens Valley and the Los Angeles Aqueduct, 1913-2013." [Link]

8. __ "Outrage in Owens Valley a century after L.A. began taking its water" by Tom Knudson. The Sacramento Bee, Jan. 5, 2014. [https://www.sacbee.com/news/investigations/the-public-eye/article2588151.html]

9. ibid.

10. ibid.

11. Prather, op.cit.

9600 dpi jpegs from digital images (photographs) by Leon Worden, May 22, 2015 | Originals on file. |

Friends of Eastern Calif. Museum Newsletter

Swansea Petroglyphs (60)

Bedrock Mortars, Independence (11)

Inyo County: 2 Indians Huddle for Warmth, 1930s

L.A. Aqueduct Construction Equipment (28)

Lake Views, Relics at Keeler (40)

From Yellow Grade Road (3)

|

The site owner makes no assertions as to ownership of any original copyrights to digitized images. However, these images are intended for Personal or Research use only. Any other kind of use, including but not limited to commercial or scholarly publication in any medium or format, public exhibition, or use online or in a web site, may be subject to additional restrictions including but not limited to the copyrights held by parties other than the site owner. USERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE for determining the existence of such rights and for obtaining any permissions and/or paying associated fees necessary for the proposed use.